By Karen de Lacey

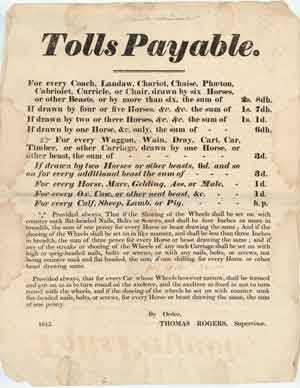

The first Turnpike Act was passed in England in 1663 but it wasn’t until 1729 that the first Turnpike Act for Ireland was introduced, allowing tolls to be charged on those travelling the road from Dublin to Kilcullen. Previously, all responsibility for roads had rested with local parish vestries and the Grand Juries, but the unrelenting growth of Dublin and the consequent damage to the roads leading to the city compelled the County of Dublin Grand Jury to advocate for an alternative system. The resultant Turnpike Acts permitted a trust to levy tolls on the different types of traffic using the turnpike road, including chaises, carriages, carts and wagons. The tolls were collected at the turnpike or toll-gate, which was leased out to individuals by the trust. The toll monies were then used by the trust to improve and maintain the road.

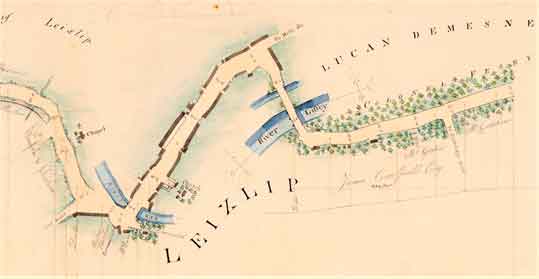

With the exception of that by David Broderick, reasonably little research has been undertaken on turnpike roads in Ireland, perhaps because so few of these records have survived. Most were held in the Public Record Office, with the result that they were largely destroyed in 1922. Dublin County Council were thankfully lax in sending the records in their care to the PRO, however, and so a considerable number are held at Fingal Local Studies and Archives in Swords. Fingal holds records for the turnpikes from Dublin to Dunleer, Malahide, Mullingar, Carlow, Knocksedan, Ashbourne and Navan. The records comprise minute-books, account books, correspondence, returns for the various toll-gates, agreements for improvement works, and leases for toll-gates and various premises along the route. There are also a small number of maps and plans.

By far the largest set of records held by Fingal relate to the Dublin–Dunleer Turnpike Trust, which oversaw a 38-mile-long route that took in Drumcondra, Santry, Swords, Balbriggan, Gormanston, Drogheda and Dunleer. Part of this road would go on to form a section of the old N1 (Dublin to Belfast) road. It had been made a turnpike by an Act of 1732. The early decades are not accounted for in the Fingal records, which, though incomplete, span the years from 1775 to 1855.

The collection is a rich source of information about the people administering, working and living on and along the road. The names of trustees, civil engineers, overseers, contractors, gate leaseholders, labourers, landowners, jaunting-car drivers and innkeepers can all be found among the documents. Some well-known names from north Dublin are present, including Edward Taylor of Ardgillan Castle, George Woods of Milverton, Charles Cobbe of Newbridge House and James Hans Hamilton of Abbottstown, who were all trustees. William Dargan, who would go on to play such a vital role in Irish railways, was hired as a civil engineer for the Trust in 1831. He may have had his mind on other things, however, as there are letters in the collection from turnpike inspector William Robinson threatening to withhold Dargan’s salary if he does not repair the sections of the Swords Road for which he is responsible. Withheld pay also features in a harrowing letter from a Michael Harford to the board of directors, claiming that he is owed £16-12–9 for work carried out. He writes that he is in the last stage of destitution and on the verge of starvation, and asks to be paid in even the ‘smallest weekly instalments’. There is no record of a reply from the board.

While the turnpike system was supposed to provide the monies required to maintain the roads, the ‘ruinous’ state of the Dublin to Dunleer road was a constant complaint in newspapers and from local people. Complaints were such a normal occurrence that the collection contains blank printed complaint forms ready to be filled in.

The Revd Alexander Nicholson from Dunleer wrote to the trust in 1816 to complain about Tiernan, the gatekeeper of the Killineer turnpike north of Drogheda, ‘one of the most impudent fellows that can be found’. Apparently, while the reverend was travelling with his wife, the gatekeeper ‘made use of the most insolent and abusive language’ and Nicholson was compelled to call him a ‘saucy scoundrel’; Tiernan returned the insult, alleging that Nicholson was ‘a much greater scoundrel’ and that he ‘did not care a damn’ for him or his complaint. A short time later, Tiernan had a run-in with Nicholson’s servant in which the gatekeeper alleged that they were both ‘scuts and rascals’. Tiernan claimed that Nicholson had aimed a pistol at him, which the latter most vehemently denied. Road rage may not just be a modern phenomenon after all.

One problem faced by the turnpikes in Dublin was that there were a variety of other roads that could be used and many travellers were happy to extend their journey time rather than pay a toll. In 1820 James Keith, who was leasing the Drumcondra toll-gate, wrote to the directors of the trust complaining that he will be in arrears for £46 as ‘the country people are totally averse to paying the … tolls’ and are using alternate roads to arrive at the Glasnevin gates, where they are allowed to pass for half the price of the gate at Drumcondra.

While the original intention was that the turnpike roads would pay for themselves, the reality was that most trusts were deeply in debt. By the 1830s a parliamentary committee had been established to report on the state of the turnpike trusts in Ireland, and in 1854 a commission of inquiry into the possible abolition of various turnpikes in Dublin began. On the opening day, the counsel for the Turnpikes Abolition Committee said plainly that ‘Turnpikes had been good in their day, but that day had passed by’. The opening of the Dublin to Drogheda railway in 1844, combined with the effects of the Famine, eventually caused such a drop in finances that the Dublin to Dunleer turnpike could no longer justifiably continue. It was abolished by an Act in 1855, with all turnpikes in Ireland abolished by 1858.

Karen de Lacey is County Archivist at Fingal Local Studies and Archives and a member of Local Government Archivists and Records Managers (LGARM).