Wasted by a sojourn in the Park?

Uachtaráin

TG4, April–May 2007

Dearg Films

by John Gibney

The presidency of Ireland is often seen as at best a figurehead and at worst a retirement home, a largely meaningless office to be respected more for its democratic and republican symbolism than for its actual value. There is a curious contrast to be made between its anodyne reputation and the individuals who have actually occupied it. And this presents a dilemma for any prospective documentary-makers: should they focus on the office, or on those who held it?

It’s a tension that this series never adequately resolves. Each of the episodes devotes itself to one of the eight presidents in a biographical approach that is generally weighted towards the portion of their life spent in Áras an Uachtaráin. The catch is that this was usually the least interesting portion of their lives. When, for example, at the end of the first episode there is an attempt to sum up the significance of Douglas Hyde, all of those asked dwell on his contribution to the Irish language without even mentioning his tenure as president. The presidency arose from de Valera’s 1937 constitution, as he sought to gradually extricate the Free State from the Commonwealth. A bizarre anomaly was that until the declaration of the republic came into effect in 1949 the office was particularly meaningless, being little more than a kind of ‘first citizen’, as the British monarch remained head of state. Hence the position was merely notional, and the first to occupy it was Hyde.

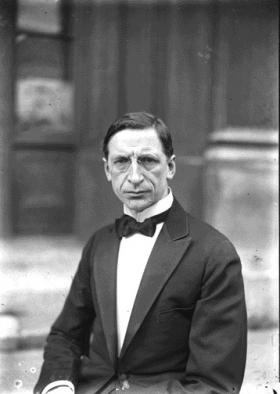

Hyde was a compelling character. From an impeccable Church of Ireland background in Roscommon, he was a multilingual polymath who cajoled much folklore from the peasantry of the west with the aid of whiskey, and his huge contribution to cultural politics was testified to by many who later became active in the struggle for independence; arguably, Hyde sent out far more men for the English to shoot than the self-serving Yeats ever did. He was appointed as the first president in the twilight of his career as a candidate acceptable to all, not least on religious grounds—though in a bitter irony no Catholic member of the cabinet would attend his funeral for fear of excommunication. Religion played a different role in the nomination of the middle-class northside Dubliner Seán T. O’Kelly to succeed Hyde in 1945. Despite having been de Valera’s right-hand man through much of the 1920s and 1930s, O’Kelly was a Knight of Columbanus and was suspected by de Valera of keeping the Catholic hierarchy inappropriately informed about government business: hence, it is argued, his marginalisation (rather than ‘elevation’) to Áras an Uachtaráin. But the plain people of Ireland liked O’Kelly, who was seen as good company and fond of a drink, complete with Guinness on draught in the Áras (though T. K. Whitaker, one of a number of ‘talking heads’ who provide lively running commentaries throughout the series, seemed to imply from his own experience that O’Kelly was a snob). On the other hand, some of the Áras staff resigned out of affection for O’Kelly on his departure rather than work for another president, a fact that stands in stark contrast to Mary Robinson’s rather callous expulsion of elderly staff from the Áras just after her own election.

O’Kelly’s successor was his old boss, de Valera, whose fourteen-year term probably did more than anything else to copperfasten the image of Áras an Uachtaráin as a retirement home, especially as he died at the age of 93, two years after leaving it. But after de Valera the office was filled by a succession of enormously capable figures, all of whom were arguably in the prime of their prospective careers. After the tenure of Erskine Childers was cut short by his untimely death, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, a former attorney general and supreme court judge, was inaugurated president by unanimous decision in December 1974, thus avoiding an election. His tenure is best known for the

controversy that forced his resignation. After the IRA’s assassination of the British ambassador, Christopher Ewart-Biggs, Ó Dálaigh referred the resulting Emergency Powers Bill to the supreme court, much to the disgust of Liam Cosgrave’s Fine Gael-led coalition. As a member of the same court since 1965 Ó Dálaigh had been instrumental in probing the limits of the constitution, but for a government that was arguing that the state was in danger of being overthrown this was an unwarranted interference—hence Paddy Donegan’s famous outburst, not the least of which was the insinuation that Ó Dálaigh had subversive sympathies. His resignation was inevitable; it remains one of the shabbier episodes of a high-handed government. Alongside a natural Fine Gael distaste for a Fianna Fáil president, the cultured and cosmopolitan Ó Dálaigh (who had made a very positive impression on a European stage when he had been appointed to the European Court) seems to have been the victim of a form of Blueshirt inferiority complex, a suggestion

bolstered by the litany of petty snubs directed at him by Cosgrave and his government.

In part this controversy accounted for the appointment of the Clare doctor Patrick Hillery to succeed Ó Dálaigh in 1976, again without an election. Hillery was seen as a safe bet. More importantly, however, his move to the Phoenix Park would remove a possible future leader of Fianna Fáil from active politics, a tactic replicated when unscrupulous Fianna Fáil elements later spread malicious rumours about Hillery’s private life in the hope, it seems, of procuring his resignation and thereby getting Jack Lynch out of the way by installing him in the Áras (the programme-makers leave no doubt as to who was probably behind this). Hillery had been a capable minister for education, labour and foreign affairs, and later Ireland’s first European commissioner: he had been hugely prominent against the backdrop of the outbreak of conflict in the north, the subsequent upheavals within Fianna Fáil and Ireland’s entry into the EEC. Yet his reluctant fourteen-year tenure seemed to symbolise the essentially hollow nature of the office. And one comes to the end of this series still wondering what the Irish president is actually for. The much-hyped presidency of Mary Robinson and the lower-key tenure of her successor, Mary McAleese, remain a little too close to judge adequately. But are they just the latest in a line of public figures to have been wasted by a sojourn in the Phoenix Park?

John Gibney is an IRCHSS Government of Ireland fellow at the Moore Institute for Research in the Humanities and Social Studies, NUI Galway.