By Richard Harrington

In late 1641, as the dispute between Crown and Parliament in England veered towards civil war, Ireland was torn apart by one of the most chaotic rebellions in its history. Spurred by fear of a Parliamentarian victory, Gaelic Irish and ‘Old English’ Catholics joined forces to overthrow English rule and reverse the encroachments on their religious freedoms and political clout that had taken place since the first plantations. Their success was neither total nor immediate, and both sides engaged in atrocities. It became hard to tell fact from fiction in the reports that came out from across Ireland and especially from Ulster: hundreds of people were locked into churches that were then set ablaze; crowds were chased into ice-cold rivers and stabbed with pikes as they tried to escape; pregnant women were cut open and butchered. Much was only rumour, but it still had the power to shock and appal. The scenes were less extreme but just as bloody in the south-east, where the quiet town of Ardmore, Co. Waterford, found itself seized by rebels only to be retaken months later. The rebellion would drag on for more than eleven years until it was finally, brutally, extinguished by Cromwell’s army, but at an early stage the Dublin administration set about documenting the losses of its loyal subjects, namely ‘New English’ Protestants, who had suffered at the hands of the rebels.

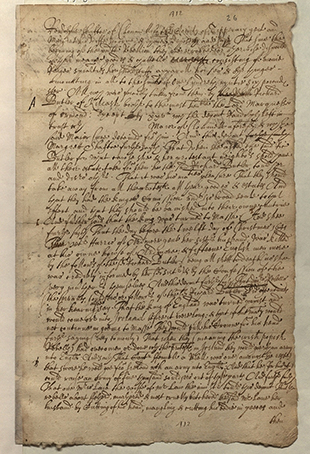

1641 DEPOSITIONS

The resulting 1641 Depositions constitute one of the most valuable textual resources on seventeenth-century Ireland. A collection of c. 8,000 sworn witness statements, they hold enormous potential as a source of social and genealogical material, in addition to their value as economic and legal records. The digitisation of the entire collection (1641.tcd.ie) has made it far more accessible to a much broader scholarship and audience.

The depositions recorded the losses of the Protestant settlers in Ireland in fine detail, whether in land, livestock, domestic goods or debts owed. It was therefore inevitable that they would serve as social commentary, yielding vast amounts of information on life in Ireland, not just for the Protestant settlers’ society but also for their servants and the Gaelic Irish. Although there is an almost complete lack of voices of Catholic victims, of whom there were undoubtedly very many, the long lists of grievances that the Protestant population aired against their neighbours and assailants help to fill that void. What we have been left with is only a partial, one-sided record of the 1641 rebellion and the Ireland in which it occurred, but it can provide the means of reconstructing and filling in much of the picture.

CLAIMS OF ROYAL SANCTION

The rebel leader Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret, was a controversial figure. A Catholic and loyalist who regularly butted heads with the administration, he had sided with the rebels against the Protestant settlers and his peers, including his own cousin, the Earl of Ormond, in protest at their refusal to allow the Old English to arm themselves in their defence. Yet this supposed chivalry is absent in the depositions from around Ardmore, where Butler’s men stole 800 sheep from a Protestant landowner, John Brelsford, and killed Brelsford’s brother-in-law, Peter Harris. When their victims demanded to know why they were being attacked and robbed, Butler’s men claimed ‘that they had authority for to doe it & that they had the kings broad seale to shew for it’, while Butler himself, according to Margret Shaftoe, a deponent from Clonmel, stated repeatedly ‘that it was his maiesties pleasure That they should take away from all the protestants all their goodes & estates’, and even claimed that the king himself had become a Catholic. Other rebels taunted their captives, saying that they would depose the king if he did not keep going to Mass, and one of their captains swore that he would lead an army of his own over to England. John Clement of Ardmore, captured by rebels and made to be their servant, was similarly told by his rebel ‘master,’ John Parnell, that the Protestants had ‘neither Kinge nor Quene for them’, otherwise support would have come from England. Such taunts may have been intended to demoralise the New English and make them believe that they had been completely abandoned, but what else they meant to accomplish is dubious. It seems strange for a commander like Butler, who by most accounts went out of his way to protect Protestants from unnecessary harm, at times even escorting them to places of safety, to have indulged in tormenting his prisoners. In any case, as Nicholas Canny notes, the deponents were quick to publicly contest the rebels’ claim of royal sanction.

CONVERSIONS

The authenticity or veracity of such taunts is not important here. What is significant is that they were plausible and that these Protestants believed that their Catholic neighbours, many of whom they knew or recognised, were capable of this malice against them. In many cases they had eyewitness accounts to back it up: Margret Shaftoe had been told by the minister’s wife, a Mrs Law, that Mr Law had been feathered, murdered ‘and most cruelly butchered’. A gory description of the butchering followed. It is understandable, then, that many of the depositions reveal a feeling of betrayal, both at the treachery of the Catholic Irish and at the still more distressing conversions to Catholicism of members of the New English communities. While some of the conversions seem almost expected by their neighbours, the conversion of leading community figures could only have come as a shock. This must have been so in the case of John Stutely, Ardmore’s curate, who converted with his family. The number of converts was sometimes surprisingly large. The deposition of Amos Godsell offered a long list of names of ‘parishoners of the seuerall parishes of Lisgenin Ar[d]more & Kinsale[beg]’ who all converted, including at least eight men and their wives and families, and this in an area with a population likely not more than a few hundred.

Deponents recognised that there were a variety of motivations inciting people to rebellion, not just the desire for political and religious freedom—which, they were compelled to admit, seemed valid concerns—but also the opportunity to recoup debts by ransacking their creditors’ properties and burning their books. The recitation of losses in the depositions, by victims looking for compensation, makes them an invaluable resource, as we are provided with reams of information on each deponent’s means, social status and connections. Even at this very superficial level we see broad contrasts emerging within the Protestant communities: Robert Holloway was robbed of thirteen pounds and five shillings (c. €2,650 today) and deprived of an annual income of ten pounds (€2,000) as clerk in Ardmore and surrounding parishes, while his fellow townsman John Brelsford incurred losses of 1,950 pounds and ten shillings (€390,000), of which a third was livestock and much of the rest was property that he held throughout the barony of Decies-within-Drum. The lists of debtors that come with these recitations show how interconnected the communities were before the rebellion: Brelsford’s debtors included men and women from all over the barony and as far afield as Dungarvan, most of whom had joined the rebellion, but he also cited ‘one English & protestant vizt Elizabeth Harriss whom is vtterly impouerished by reason of this present rebellion’. Though some of the rebellion’s leaders remained aloof from the ransacking, it was inevitable that other participants would take it as an opportunity either to exact retribution for past grievances or simply to acquire plunder for themselves.

MURDER AND RUMOUR IN ARDMORE

In comparison to the atrocities committed elsewhere, the Ardmore depositions are quiet, though far from silent. Protestants in the parishes of Ardmore and Lisgenan (Grange) were robbed and despoiled, and on 5 January 1642 there was a murder in Ardmore. The victim was a local man, Peter Harris. This episode displays the ‘Chinese whispers’ effect as knowledge of the murder spread along networks of kin. In Ardmore, Harris’s brother-in-law John Brelsford, who seems to have been present and was himself taken prisoner, stated that Harris had been killed ‘at the Castle of Ardmore’ by men under one of Butler’s lieutenants. Margret Shaftoe of Clonmel, ‘credibly informed by her sister’, testified that he had been killed at his own home, as well as ‘fifteene English men more by the followers of the said Richard Butler’. Shaftoe’s sister was Harris’s wife. Finally, Elizabeth Fleming, a deponent from Grange—about two miles from Ardmore—said that Harris had been killed near the village, ‘at the gate of Ardmore … but by whome shee knoweth not’. Although Fleming was far closer to Ardmore than Shaftoe, her knowledge of the incident was incomplete and likely based on hearsay or gossip. Shaftoe seems to represent an intermediary level of knowledge between Fleming and Brelsford. This shows another key benefit of the depositions: the fact that so many were taken from so many witnesses can allow us to cross-reference statements and build a more complete picture of events.

The depositions are in many cases our only evidence for events which must have been calamitous for the people who experienced them. The murder of Harris alone would have made 1642 an annus horribilis in Ardmore, but depositions from around Ardmore reveal that worse was yet to come.

ARDMORE UNDER SIEGE (TWICE)

On 1 March 1642, the royalist captain Symon Bridges captured a rebel messenger, ‘whome he instantly executed’, as he was marching to Dungarvan. The messenger had ‘a letter in his pocket writtn by James Waylsh a reputed Capt: among the Rebbells’. Walsh’s family had strong rebel convictions: his father Nicholas Walsh, of nearby Pilltown, had been accused of forging the ‘king’s broad seale’ that lent legitimacy to the rebels’ atrocities. James Walsh was laying siege to Ardmore and had written to Butler, his commander, advising that he had sent him ‘twenty English mens cowes’ and needed supplies of gunpowder for the siege. It seems that Ardmore fell to the rebels, because in a deposition given in June 1642 Robert Holloway remembered seeing the proselyte John O’Hay, a former Protestant who had converted to Catholicism, ‘in arms among the rebells, when the Castle of Ardmore was takn’. The captive John Clement also recalled later that his ‘master’ had been ‘one of those that tooke the Castle of Ardmore from the English’. This first siege appears in no other primary sources and, as far as I am aware, has not been noticed in any histories of Ardmore. But for the depositions it would have gone entirely unrecorded.

The castle gave the rebels control of much of Waterford and allowed them to safely bring in the harvest to provision their armies. Moreover, it effectively prevented royalists from crossing the Blackwater, so it was not destined to remain in rebel hands uncontested. Sure enough, on 26 August 1642 a royalist army from Lismore marched south to Ardmore. It was led by the brothers Richard and Roger Boyle, sons of the Great Earl of Cork, and a royalist account of the siege that followed was written up shortly afterward by ‘a worthy gentleman who was present’. John Windele republished this entire account in 1856. Although the castle has long since disappeared and its location remains a mystery, it must have been quite substantial. It was garrisoned with 100 soldiers, as well as the sheltering populace, and the royalists, 400-strong, ‘expected not to gain it, but after a long Seige’. They encircled the castle, as well as Ardmore’s round tower, which was also garrisoned against them, and awaited the arrival by sea of a culverin (a long-barrelled cannon) for which they had sent. There was gunfire from the rebels, but the royalists captured the castle’s outbuildings, including the cathedral, and cut the defenders off from their supplies. A rebel army drew near on the following morning, possibly hoping to relieve the siege, but fled towards Dungarvan when the royalists moved to engage them. They pursued until their horses were unable to traverse ‘a Glinne betwixt us and them’, probably the glen of the River Licky, and withdrew to continue the siege.

The culverin arrived at noon on the second day, and over the next three hours they advanced it under cover of wool-packs that they carried to avoid getting shot. Before they could fire on the castle, its commander asked for a parley. He requested quarter. This was refused, so he submitted to the attackers’ mercy. The rebels in the round tower, though they only had two guns among 40, held out until they had conferred with their commander and then surrendered. Over 100 of the rebels were hanged the next day. The siege had lasted only 24 hours but was likely the bloodiest and most dramatic moment in Ardmore’s history.

Richard Harrington is a Ph.D student studying medieval Ardmore at University College Cork.

Further reading

N. Canny, ‘What really happened in Ireland in 1641?’, in J. Ohlmeyer (ed.), Ireland from independence to occupation, 1641–1660 (Cambridge, 1995).

M.-L. Coolahan, ‘“And this deponent further sayeth”: orality, print and the 1641 Depositions’, in M. Caball & A. Carpenter (eds), Oral and print cultures in Ireland, 1600–1900 (Dublin, 2010).

J. Windele, ‘The round tower of Ardmore, and its siege in 1642’, Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society (new ser.) 1 (1) (1856).