By Daniel Mulhall

In the opening episode of Ulysses at the Martello tower in Sandycove, we tap into Stephen Dedalus’s exchange with the Hibernophile Englishman Haines, in which Stephen describes himself as a subject of two masters, ‘the imperial British state’ and ‘the holy Roman catholic and apostolic church’. And, he adds sourly, ‘a third who wants me for odd jobs’, which is clearly a reference to Irish nationalism.

There were not many years as eventful for nationalist Ireland as those between 1921 and 1923. That time saw the end of the War of Independence, the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Sinn Féin split, the birth of the Irish Free State and a damaging civil war. Those were also years of terrific achievement for Irish literature, with the appearance of major works by W.B. Yeats and Seán O’Casey. And, of course, James Joyce published Ulysses on his 40th birthday in February 1922. One way of seeing Ulysses is as Joyce’s ‘history novel’, whose pages plunge into the rich pool of Irish history in the period between the death of Parnell in 1891 and the 1916 Rising. Ulysses is set in June 1904, at roughly the halfway point between those two momentous dates in modern Irish history

‘HISTORY IS TO BLAME’

In Ulysses, Haines muses that ‘history is to blame’. Indeed, what Joyce saw as the burden of Irish history was part of what prompted him to leave Ireland in 1904. In A portrait of the artist as a young man, which can be seen as an extended prelude to Ulysses, Joyce wrote that Stephen, his alter ego, intended to leave Ireland to escape the ‘nets’ of language, nationality and religion. For Joyce, those ‘nets’ were tightening in early twentieth-century Ireland, a time when the Gaelic League had become something of an obsession for many of Joyce’s contemporaries, who flocked to Irish-language classes and, like Miss Ivors in his short story ‘The Dead’, began holidaying in the west of Ireland.

In 1900 the polemical Irish journalist D.P. Moran established The Leader magazine to promote the idea of an Irish Ireland. Moran concluded that ‘The foundation of Ireland is the Gael, and the Gael must be the element that absorbs’. Moran’s lofty Gaelic/Catholic ambitions for Ireland never quite came to pass, but his exclusivist views made life uncomfortable for those like Joyce who wanted Ireland to be more European. In the raucous ‘Cyclops’ episode of Ulysses Joyce lampoons the Irish-Ireland ethos.

Joyce, who was a contemporary of the 1916 leaders Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and Eamon de Valera, resolved that Stephen would not serve his ‘fatherland’ or his ‘church’ but would defend his artistic integrity using what he referred to in A portrait as ‘silence, exile and cunning’. Ulysses can be seen as an elegy for the country Joyce left behind, a country at the butt-end of the post-Parnell era and with a new age in the thick of what Yeats later called its ‘long gestation’ in the decades prior to 1916.

‘HISTORY IS A NIGHTMARE’

In the novel’s second episode, set in a school in Dalkey, Stephen tells its principal, Mr Deasy, that ‘history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake’. Part of Stephen’s historical nightmare stemmed from the precipitous fall of Parnell and his death in 1891. Through his father, an ardent Parnellite, Joyce acquired an enduring fascination with Parnell. In a Trieste newspaper, Joyce wrote about the ‘extraordinary personality of a leader who, with no forensic gift or original political talent, forced the greatest English politician (Gladstone) to follow his orders’. As he put it, Parnell ‘united every element of national life behind him and set out on a march along the borders of insurrection’—or, as Joyce’s character Henchy captured it more punchily in ‘Ivy Day at the Committee Room’, ‘He was the only man that could keep that bag of cats in order’.

The Irish people, in Joyce’s caustic view, had thrown Parnell ‘to the wolves’. The hopes of Joyce’s father’s generation had been dashed in the process. The Dictionary of Irish biography’s entry on Joyce senior states that ‘The fall of John Joyce coincided with the political fall and death of Parnell whom John Joyce (and his son) vigorously supported. John took little interest in active politics after this, even after the Irish Party reunited. The family moved from their comfortable middle-class life to more difficult circumstances on the north side of Dublin.’ This links the decline of the Joyce family directly with the political disappointments that ravaged turn-of-the-century Ireland in the wake of Parnell’s fall.

In the ‘Eumaeus’ episode, when Bloom tries to encourage Stephen to engage with Irish affairs, the younger man responds with a conversation stopper: ‘We can’t change the country. Let us change the subject.’ Nonetheless, the country Joyce left in 1904 became his sole subject for the remainder of his writing life.

BLOOM’S NATIONALISM

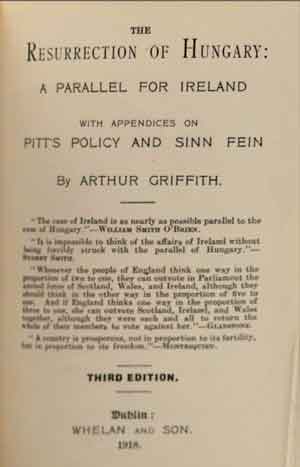

Joyce’s twentieth-century Everyman, Leopold Bloom, though preoccupied with his wife’s looming infidelity, keeps a weather eye on Irish public life. There are glimpses of future developments in Bloom’s admiration for Arthur Griffith, whom he views as a ‘coming man’. Joyce thought Griffith’s United Irishman to be the only journal of value in Ireland. In an essay published in Italian in a Trieste newspaper, he described Griffith’s Sinn Féin as the latest iteration of the Fenian tradition. In the ‘Cyclops’ episode, Joyce has John Wyse Nolan state that Bloom had given Griffith the idea for his 1904 political tract The resurrection of Hungary. In her soliloquy Molly, who has a down-to-earth view of things, dismisses Griffith and tells us that Bloom has been ‘going about with some of them Sinner Fein lately or whatever they call themselves talking his usual trash and nonsense’.

We also learn from Molly that Bloom once harboured ambitions to stand for parliament, and in the ‘Circe’ episode there is an extravagant fantasy in which he is presented as a successor to Parnell. In his imaginary manifesto—earnest and idealistic—Bloom stands for ‘the reform of municipal morals and the plain ten commandments. New worlds for old. Union of all, jew, moslem and gentile. Three acres and a cow for all children of nature … No more patriotism of barspongers and dropsical impostors. Free money, free love and a free lay church in a free lay state.’ Could that be an agenda for a United Ireland?

BLOOM VS ‘THE CITIZEN’

The novel’s ‘Cyclops’ episode features a glorious set-to between Bloom and ‘the citizen’ (based on GAA founder Michael Cusack), and I thoroughly recommend that comical verbal rant to readers looking for a free-standing flavour of Joyce’s novel. ‘Cyclops’ seems to me to be crucial in identifying Leopold Bloom as an apostle of tolerance and moderation in a world trending towards extremes. Bloom defines a nation pragmatically as ‘the same people living in the same place’; when asked by ‘the citizen’ ‘what is your nation’, he responds defiantly and with a pragmatic definition: ‘Ireland, I was born here, Ireland’. By contrast, many of Joyce’s contemporaries tended to view national identity as a compound of cultural, ethnic and religious homogeneities.

Joyce gives us an extended exposure to ‘the citizen’s’ vigorous opinions. He takes aim at ‘the bloody brutal Sassenachs’ and rehashes the full slate of nationalist grievances against British rule—the curtailment of Ireland’s economy, the ravages of emigration and population decline, even deforestation. King Edward VII, who visited Ireland in 1903, becomes a prime target as the exchanges in Barney Kiernan’s pub on Little Britain Street become more and more uninhibited: ‘there’s a bloody sight more pox than pax about that boyo’ is just one example of the colourful invective that swarms through this episode.

The balanced, reasoned arguments voiced by Bloom get nowhere against the adamantine ‘citizen’, who wields his sound bites well. ‘The memory of the dead and Sinn Fein amhain! The friends we love by our side and the foes we hate before us.’ Joyce’s portrait of Cusack is, of course, an unfair caricature in which ‘the citizen’ is used to epitomise a brand of nationalism that flourished in the early twentieth century, and not just in Ireland.

For me, the key moment in Ulysses comes when Bloom, for the only time in the novel, cuts loose with sharp views of his own.

‘But it’s no use, says he. Force, hatred, history, all that. That’s not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it’s the very opposite of that that is really life.

—What? says Alf.

—Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred.’

I see this appeal to transcend force, history and hatred as a key statement of Bloom’s and Joyce’s credo.

BLOOM VS ‘SKIN-THE-GOAT’

In the ‘Eumaeus’ episode, Bloom’s prudent opinions are set against those of a character who may (or may not) be ‘Skin-the-Goat’ Fitzharris, a member of the Invincibles who killed the chief secretary of Ireland, Lord Cavendish, in the Phoenix Park in May 1882, the year of Joyce’s birth. The Invincibles were on Bloom’s mind earlier in the day when, visiting a church, he muses on the fact that James Carey, ‘that fellow that turned queen’s evidence on the Invincibles’, had received communion there every day and ‘plotting that murder all the time’. In the ‘Cyclops’ episode, the execution of the Invincible Joe Brady is recalled.

‘Skin-the-Goat’ is the only character in Ulysses who represents the Fenian strand of the nationalist tradition. He relishes the prospect of England’s fall from grace when the Germans and the Japs have ‘their little lookin’. ‘The Boers’, he insists, ‘were the beginning of the end’, and Ireland would be England’s ‘Achilles heel’. That was part of the thinking that inspired the Easter Rising—the opportunity to strike while Britain was preoccupied with wider challenges.

Bloom pooh-poohs Skin-the-Goat’s claims as ‘egregious balderdash’ and thinks it ‘highly advisable in the interim to try to make the most of both countries, even though poles apart’. Bloom is one of life’s pragmatists, always looking for compromise at a time when such views were increasingly out of season in a world on the precipice of war and revolution.

The sailor, W.B. Murphy, reminds Skin-the-Goat that the Irish had long fought in significant numbers in the British Army—‘the Irish catholic peasant. He’s the backbone of our empire.’ Bloom agrees with this: ‘Irish soldiers had as often fought for England as against her, more so, in fact’. Skin-the-Goat replies that no Irishman worth his salt would join the British army. That became sensitive ground as the pros and cons of wartime enlistment split nationalist Ireland in 1914. While writing Ulysses, Joyce would have been well aware of the sacrifice of those Irishmen fighting in British uniform in the First World War. His schoolfriend Tom Kettle, a former MP, was killed on the Western Front in 1916.

Bloom is opposed to violence but couldn’t help feeling ‘a certain kind of admiration for a man who had actually brandished a knife, cold steel with the courage of his political convictions though personally he would not be party to any such thing’. Bloom, therefore, understands the appeal of physical-force nationalism but turns away from it:

‘I resent violence or intolerance in any shape or form. It never reaches anything or stops anything. A revolution must come on the due installments plan. It’s a patent absurdity to hate people because they live round the corner and speak another vernacular, so to speak.’

Bloom is inclined to attribute ‘those wretched quarrels’ to ‘the money question’. In a nod to what would now be described as a universal basic income, he wants ‘all creeds and classes’ to have ‘a comfortable, tidysized income’ which would ‘be provocative of friendlier intercourse between man and man … I call that patriotism’. Here we get an inkling of Joyce’s own socialist leanings as well as a focus on an aspect of Irish nationalism that was neglected in the pre-independence period—the economics of self-government.

CONCLUSION

Although it is not his primary role, Bloom turns out to be a perceptive witness to the complex politics of Ireland in the early twentieth century. He engages with the various strands of early twentieth-century Irish nationalism—parliamentary (through the Parnell legacy), Irish Ireland (through ‘the citizen’), Sinn Féin (through Griffith) and Fenian (through Skin-the-Goat). If forced to hazard a guess, I would say that Bloom, and by extension Joyce, was a Parnellite Sinn Féiner of 1904 vintage.

Leopold Bloom’s Ireland is set on a cusp between the fading Parnellite world and the more combative nationalism of the decade that followed. I see Ulysses as an inquest into the dashed Parnellite hopes of Joyce’s father’s generation. Joyce wrote his novel in the years during and after the First World War. Mr Cautious Calmer, as Bloom is called in the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ episode, is a middle-of-the-road nationalist, an outlier in a world of narrowing nationalisms. He is an Everyman for our time too, an age when ‘force’, ‘hatred’ and the abuse of ‘history’ are getting more than ‘a little lookin’ in this third decade of the 21st century.

Daniel Mulhall is a retired Irish ambassador whose latest book is Pilgrim soul: W.B. Yeats and the Ireland of his time (New Island Books, 2023).

Further reading

J.M. Hassett, The Ulysses trials: beauty and truth meets the law (Dublin, 2016).

V. Igoe, The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: a biographical guide (Dublin, 2016).

D. Mulhall, Ulysses: a reader’s odyssey (Dublin, 2022).