By Laurence Geary

Smallpox or variola is the only human disease to have been eradicated by vaccination, the last natural case occurring in 1977. For centuries this acute, highly infectious viral disease was feared and loathed in Ireland and elsewhere because of its disfiguring effects and relatively high mortality rate, often around 20%. Except in the rarest instances, there were only two ways in which smallpox infection could end—death or long-term protection against recurrence.

Variolation vs vaccination

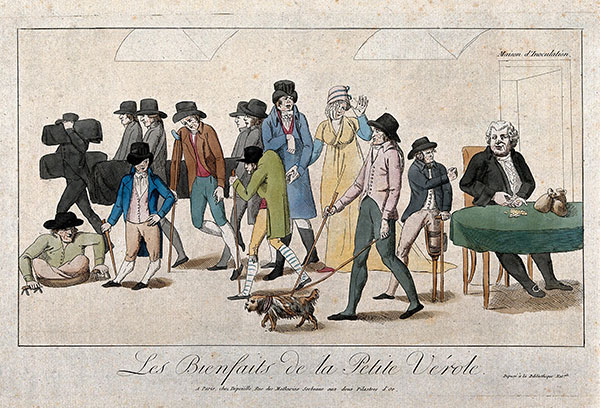

It was known that smallpox could be prevented by variolation—the inoculation or artificial infection of healthy people with smallpox matter in the hope of producing a mild case of the disease and immunity from future contagion. The procedure, which originated in China, was introduced to Britain in 1721 and to Ireland a few years later. Variolation was generally accomplished by obtaining fluid from pustules of an active case of smallpox and scratching it into the skin, a process popularly known in Ireland as ‘cutting’ and frequently performed by unlicensed itinerant inoculators for a fee. Variolation protected the recipient but exposed the general population to the possibility of contracting fully virulent smallpox, and thus posed a serious threat to public health.

The identification and promulgation of vaccination (from vacca, Latin for cow) in the late 1790s by Edward Jenner, an English West Country doctor, was a significant advance. Jenner noticed that farm workers who contracted a mild pox disease from livestock, usually from milking infected cows, were subsequently immune to natural and inoculated smallpox. The technique employed in vaccination and variolation was identical, but vaccination conveyed cowpox, which was safer and more effective than smallpox.

Earliest vaccinations in Ireland

John Milner Barry, a Cork medical practitioner, was among the first in Ireland to recognise the importance of the new procedure. He obtained a silk thread steeped in vaccine by post from a colleague in London, and on 6 June 1800 vaccinated six children in Cork by raising the skin with a lancet and inserting a portion of the vaccine-infused thread, which he secured with a sticking plaster. Barry obtained sufficient doses of cowpox infection from these children to vaccinate others in the city and its environs, and in the following months he and a colleague immunised more than 300 children. Although Barry is generally credited with introducing vaccination into Ireland, the procedure had been performed at the Dispensary for Infant Poor in Dublin since its establishment in March 1800.

The popular awareness in the west of England of the prophylactic power of cowpox, which informed Jenner’s vaccination experimentation, also pertained in eighteenth-century rural Ireland. In a pamphlet published in Cork in 1800, Barry observed that for the previous half-century and more country people were familiar with cowpox, which they termed ‘shinach’, from the Irish word sine, meaning teat (of an animal); they recognised the mildness of the cowpox infection and its ability to provide immunity from smallpox. Cowpox appears to have been endemic in mid- and west Cork—and probably in other parts of Ireland also—in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, and country people purposely exposed themselves to the disease, such was the general belief that those who contracted cowpox were ever after protected from the more virulent smallpox. Barry recorded the experiences of several individuals who were intentionally exposed to cowpox infection as children: 50-year-old Joanna Sullivan, for instance, who recalled that, as a thirteen-year-old, she and several other children were taken to a dairy and made to squeeze the cows’ teats until their hands were covered with ‘the fluid matter of the disorder’, known to them as the ‘shinach’.

Barry’s pamphlet on vaccination, in addition to its significance as a medical text, contains the case histories and oral testimony of many country people, accounts that shed light on other popular beliefs and practices in eighteenth-century County Cork. Barry noted that women alone milked cows and that men dissociated themselves from the work, considering it demeaning to participate in any rural occupation involving women, from which we might reasonably infer that women—at least those engaged in dairying—were more immune to smallpox and its consequences than men.

Opposition

Irish medical practitioners and the country’s wealthier and better-educated classes were generally receptive to vaccination, but there was solid resistance to the practice among the rural poor for much of the nineteenth century. Despite the best efforts of the medical profession and the clergy, the old method of variolation persisted in the countryside—in Munster, Ulster and particularly in Connacht—where itinerant smallpox inoculators, intent on safeguarding a lucrative practice, preyed on the fears and prejudices of the peasantry, thereby ensuring that smallpox mortality remained high, particularly among infants and children.

Several surveys in the first half of the nineteenth century indicate that outbreaks of smallpox were frequent, extensive and lethal, and largely attributable to itinerant inoculators. Some licensed medical practitioners were also indicted for their adherence to what most of their professional colleagues regarded as a dangerous and discredited practice. In the early 1830s, for example, at least 225 children in Doneraile, Co. Cork, died of smallpox following variolation by the local apothecary. In 1832 the Bantry dispensary doctor variolated almost 1,300 individuals in west Cork and continued the practice privately thereafter. In Drogheda some licensed medical practitioners persisted with variolation, much to the dismay of their colleagues, who described their activities as ‘reprehensible’.

1840 Vaccination Act

Variolation was made illegal under the Vaccination Act of 1840, but the Irish legislation was defective and largely ineffective. The maximum penalty that could be imposed was one month’s imprisonment on summary conviction, which proved to be an insufficient deterrent. When fatalities ensued and the charge was increased to one of manslaughter, judges seemed strangely reluctant to impose commensurate sentences. In July 1856, for example, Thomas Carroll and Walter Regan were convicted at the Galway summer assizes of the manslaughter of several children by inoculating with smallpox virus. The judge commented on the seriousness of the offence, which he said was punishable by transportation, and, having threatened offenders with the full rigour of the law, sentenced the defendants to two months’ and three weeks’ imprisonment respectively.

Large numbers of children, often several hundred at a time, continued to be variolated in the post-Famine years. The prevailing belief among the rural poor, and increasingly among their urban brethren, was that variolation was a superior procedure to vaccination. Accordingly, the labouring and farming classes were reluctant to cooperate with the authorities in their efforts to enforce the 1840 legislation, and they harboured and protected smallpox inoculators, even when wanted on capital charges. The latter went to considerable lengths to conceal their identities and thus avoid detection and prosecution. Many inoculators adopted disguises, at least one arraying himself in what was termed ‘woman’s attire’. Some preserved their anonymity by compelling parents and children to wear blindfolds, others negotiated with parents through intermediaries, and a few resorted to more forceful methods, threatening or physically assaulting those who wished to abide by the law.

Compulsory vaccination

The 1840 Vaccination Act failed to curb inoculation with smallpox matter, nor did it meet with any great success in extending the practice of vaccination, which was its primary purpose. It was only when vaccination was made compulsory almost a quarter of a century later that real progress was made. Under the 1863 Vaccination Act, parents or guardians of children born after 1 January 1864 were obliged to have them vaccinated by the dispensary doctor within six calendar months of birth, on pain of a fine of ten shillings, which was a considerable imposition on poor people. The effect was dramatic, the number of deaths from smallpox falling from 854 in 1864 to 20 in 1869, a decrease that helped transform popular Irish attitudes to vaccination. In April 1871 Sir Dominic Corrigan, possibly the most renowned of Ireland’s nineteenth-century medical élite, testified before the select committee on vaccination in England that the Irish now regarded the practice very positively: ‘The feeling of the whole country is in favour of it,’ he observed.

There remained, however, a huge cohort of unvaccinated people in Ireland, a situation compounded by self-interested smallpox inoculators whose interventions continued to propagate the disease. These factors were largely responsible for virulent smallpox epidemics in 1872 and 1878 which claimed more than 4,000 lives, an outcome that further raised awareness among politicians and the population generally of the deleterious impact of smallpox inoculation on public health. The first epidemic was followed by a massive vaccination programme—more than a quarter of a million people in 1872, which was an increase of almost 2,800% on 1870. Almost half of the newly immunised were born before the compulsory vaccination date of 1 January 1864. The second epidemic provided the stimulus for further ameliorative legislation. During the parliamentary debate on the bill, Mitchell Henry, MP for Galway County and a former practising surgeon, stated that the most recent smallpox outbreak had frightened people into flocking from all parts to be vaccinated. ‘The epidemic in the west of Ireland was stamped out entirely from the enthusiasm of the people in favour of vaccination,’ he claimed.

Among other provisions, the 1879 Vaccination Act reduced the period for immunising newborn babies from six months to three, further limiting the potential for smallpox epidemics among the infant population. Earlier legislation, in 1868, had increased the maximum penalty for inoculating with smallpox virus from one month’s imprisonment to six, thereby rectifying the inherent weakness in the anti-variolation clauses of the 1840 Act. Additionally, in light of the positive results generated by compulsory vaccination, judges began to impose much stiffer penalties in cases of manslaughter arising from smallpox inoculation. In one such case, in 1875, the accused was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment, a very significant advance on the penalties hitherto imposed, notably the risible sentences of two months’ and three weeks’ imprisonment handed out to Carroll and Regan a decade earlier.

Conclusion

In the second half of the nineteenth century, legislation relating to vaccination, its interpretation and implementation by the judiciary and enforcement by the constabulary, and sceptical attitudes towards the procedure itself among the rural and urban poor each underwent positive and progressive change. The increasingly robust attitude of the legislature, the judiciary and the police to the wilful propagation of smallpox, the virulence and mortality of the epidemics of the 1870s, and the continuing decline in smallpox mortality from the close of that decade onwards convinced even the most recalcitrant that vaccination was a safer and more effective prophylactic than variolation. In 1889 no deaths from smallpox were recorded for the first time in the official returns for Ireland. Although many years were to pass before the disease was finally extirpated from the country, the curtain had descended on inoculation with smallpox virus. The elimination of a dangerous practice, one that had been deeply entrenched among the rural population for generations, occurred within the vortex of modernisation in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ireland.

Laurence Geary lectured in history at University College Cork prior to his retirement.

Further reading

J.M. Barry, An account of the nature and effects of the cow-pock, illustrated with cases and communications on the subject; addressed principally to parents, with a view to promote the extirpation of the small-pox (Cork, 1800).

D. Brunton, ‘The problems of implementation: the failure and success of public vaccination against smallpox in Ireland, 1840–1873’, in G. Jones & E. Malcolm (eds), Medicine, disease and the state in Ireland, 1650–1940 (Cork, 1999).