By John Gibney

In November 1971 Harold Wilson, the former (and future) British prime minister whose Labour Party was then in opposition, visited Dublin, where he attended a dinner hosted by Taoiseach Jack Lynch. Also present was Minister for Foreign Affairs Patrick Hillery, who wrote that ‘the impression I had left was one of almost nausea at the lack of understanding of Irish politics and the extraordinary attitude to Irish people that even a well-intentioned person in English politics can have’.

A case in point was, apparently, Wilson asking Lynch, ‘Jack, did you ever think of going back into the Commonwealth?’, which met, to put it mildly, a lukewarm reception. Wilson, noted Hillery, went on to quip that

‘… “we will have the bar open all the time”, referring back to his idea of the finish of the Free Trade Area Agreement which is written in his Memoirs and relates that the final decision was only made when the Irish were told the bar was shutting soon. Those participating in the Free Trade Area negotiations were Seán Lemass who very seldom took any drink, me—I was not taking any drink at all—, and Charlie Haughey who was not interested in drink, who was more interested at that stage in getting a good bargain. However, I mention it to show how big a gap there is between him and the Irish mind.’

This encounter came in the early years of the Troubles, which inevitably loom large in the latest instalment of the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP) series, covering the years 1969–73, which lays out in comprehensive detail, and using many never previously published documents, the evolving response of Jack Lynch’s Fianna Fáil government to events in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 1973. The selection is intended to illuminate how decisions were reached while also providing a window into key events from an Irish perspective.

BRITISH ATTITUDES ALSO REFLECTED IN THE DOCUMENTS

One discrete category of document consists of those that record meetings between Irish and British officials and politicians, which had been a fact of life since Irish independence but were given a new and unwelcome impetus with the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland from August 1969 onwards. Given that these are Irish documents, retained for the most part in Ireland’s National Archives and composed by Irish diplomats and politicians, they naturally encapsulate an Irish point of view. Nevertheless, what they also reflect is the attitudes with which those Irish diplomats and politicians were presented by their British counterparts on the other side of the table, and how some of those attitudes evolved in the early years of the Troubles, as both sides sought to state one another’s position and, over time, to tease out and explore them more fully.

The Irish government had reservations about how Northern Ireland was governed and, as conflict seemed to loom on the horizon, they sought to impress upon the British the need for a change of course. Hillery became minister for foreign affairs in the summer of 1969, and that August, in the run-in to the Apprentice Boys parade in Derry that led to the Battle of the Bogside and to the deployment of British troops, he had raised his concerns with the British about how matters seemed to stand in Northern Ireland. These included provocative parades and policing; the necessity for an end to the traditional discriminatory practices of the Northern Ireland government;and the prospect of violence and civil unrest breaking out that might also have a serious impact on both sides of the border. Hillery, however, was bluntly told that Northern Ireland was an internal matter for the United Kingdom and was none of the Irish government’s business.

In strictly legal terms, the British had a point and there was little that Hillery or Lynch could do about this. The Irish Defence Forces were in no position to intervene (though in dire circumstances in which nationalists risked being massacred they would almost certainly have had to) and the British had overwhelmingly superior military forces; moreover, a cross-border incursion into the territory of a NATO member during the Cold War was hardly likely to win international sympathy. Irish attempts to bring the crisis before the United Nations received a hearing but little else. By the end of 1969 it was clear that the Irish government did not have the power to compel the British to make the shifts in policy that it felt were essential to resolve the situation, and international sympathies were not going to translate into active support. All that Irish politicians and officials could realistically do to influence how their British counterparts dealt with what was happening in Northern Ireland was to use persuasion as best they could, which gave face-to-face meetings between the two sides an added relevance.

CORDIAL?

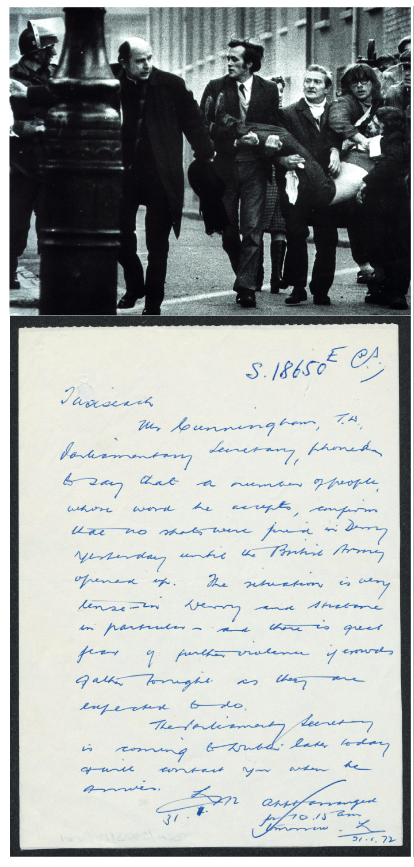

While these British–Irish meetings were often described as cordial, the record from the Irish side relates British incomprehension and misunderstanding alongside officiousness, and occasionally an arrogance bordering on belligerence, with the British usually taking an uncompromising line towards Irish complaints about repression and the heavy-handedness of their forces.In the immediate aftermath of the British Army killing of thirteen civilians in Derry on Bloody Sunday in 1972, Charles Whelan of the Irish embassy in London called on Kelvin White of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, who

‘… asked me whether we were not prepared to accept that the Army had merely returned the fire of gunmen and nail bomb throwers. I said that our Government had their own reliable sources of information, backed by the accounts of neutral observers such as newspaper men and that these contradicted the Army statements. At this stage Mr White asked me whether I was saying that the Army was telling lies. If so, there was not much point in our continuing to discuss the matter … Mr White maintained that the Army record must be accepted … He said that it seemed to him that we were now lecturing the British Government on how they should carry out policy within the United Kingdom and this was hardly acceptable.’

Such British attitudes often came to the surface. Even as they sought to influence the British as best they could to take on board nationalist concerns in Northern Ireland, Irish officials and politicians were under no illusion that the British would act in a way that suited them. When, in September 1972, the British mused that the Irish authorities might arrest the Provisional IRA leadership to take them out of circulation, it was not lost on some Irish officials that the British had managed not to arrest the same leaders when they had secretly ferried them to London for talks earlier that year.

BRITISH ESPIONAGE

The hints of British espionage that appear in some of the documents are a similar case in point. Even in August 1969 US diplomats had told their Irish counterparts that they suspected that the British had phone lines from Ireland tapped, and in December 1972 the secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Hugh McCann, called in the British ambassador, Sir John Peck, because‘an attempt has been made to suborn and subvert a member of the Garda Síochána by one or more people working for the British Department of Defence … the Taoiseach had asked him to convey to the [British] Ambassador the Taoiseach’s personal disappointment in so far as this activity betrays a lack of confidence in the relations that should exist between two friendly governments’.

McCann’s last line hints at the stark fact that, despite such British activities, it was inevitable that the Irish government had to engage with the British to find a settlement that might end the conflict. This reality lay behind the Irish attempts from late 1969 onwards to cultivate relations with British political and media figures, and to prevail upon them as best they could to do what they felt needed to be done to secure a settlement.

EDWARD HEATH

The documents printed in DIFP also reveal hints that at least some British figures were prepared, over time, to consider the Irish perspective on the Troubles, and came to accept that this might be worth taking on board. This is illustrated by two accounts by the ambassador to London, Donal O’Sullivan, of encounters with the Conservative leader, Edward Heath. In April 1970 Heath (still in opposition) met O’Sullivan in his office ‘with the greatest coldness … it was clear to me from the start that Mr Heath had decided to use the occasion of our meeting to administer a sharp dressing-down to me on the Northern question’. Yet in August 1972 O’Sullivan recorded a meeting in which Heath—now prime minister—was ‘very friendly throughout’, having interrupted a dinner party to meet O’Sullivan, and who

‘… interjected to say that I was assured there could, in any event, be no question of a return to the type of Unionist domination which previously existed. Mr Heath was quite specific in saying that that would certainly not happen…He then talked freely about reunification, which he is confident must come about. The British Government will put no obstacle in the way of reunification once the will for it exists.’

As Heath saw O’Sullivan out, he‘said he knew that “Jack Lynch is a good friend”’. The change in tone was evident.

What was also evident was a change in substance. In 1969 the Irish government had been told that Northern Ireland was none of its business. In August 1972 O’Sullivan recorded Heath considering the prospect of the Irish government being officially consulted on Northern Ireland; within months the British were talking quite openly, and officially, about an ‘Irish dimension’ to a political settlement, even as their policy was evolving amidst a climate of growing anti-Irish feeling in Britain as a reaction to IRA violence in Britain and Northern Ireland. Some of the steps that led to this shift, and much else besides, are revealed in the archival material newly published in volume XIV of Documents on Irish Foreign Policy.

John Gibney is Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy programme.

A selection of documents published in DIFP XIV will be on display in the National Archives, Bishop Street, Dublin 8, until the end of January 2025.