‘Undeterred by the dread of infectious diseases, undismayed by degrees of filth, stench, and darkness inconceivable, by those who have not experienced them’, the Revd William Whitelaw and his assistants ‘explored, in the burning months of the summer of 1798, every room of these wretched habitations [of Dublin], from the cellar to the garret, and on the spot ascertained their population’.

Ironically Whitelaw’s task was made possible by the disturbed state of the country occasioned by the United Irish rebellion of 1798. As a security measure the Lord Mayor of Dublin ordered that a list of inhabitants be affixed to the door of every house in the city. Thus the task of census-taking was a fairly straight-forward one of totting up the number of names — but only in the ‘middle and upper class’ (Whitelaw’s terms) districts of the city where the rate of literacy was high; in the ‘lower class’ districts, which accounted for the bulk of the population, Whitelaw encountered ‘a confused chaos of names, frequently illegible, and generally short of the actual number by a third, or even one-half’. At first he imputed the discrepancies to design, but was afterwards convinced that it proceeded from ‘ignorance and incapacity’. Hence the necessity for a more intrusive approach.

Much to his own surprise, Whitelaw experienced little opposition, partly as a result of the effectiveness of the government’s reign of terror against suspect rebels, and partly in consequence of a rumour that the census of the poorer districts was the prelude to the adoption of some system of poor-relief, a rumour no doubt encouraged, if not initiated, by Whitelaw himself. One serious assault did occur: an irate butcher in Ormond Market, on being quizzed on the incorrectness of his return, flung a quantity of blood and offal at an unfortunate assistant! Apart from that the main problem facing the assistants was to satisfy Whitelaw himself, a meticulous taskmaster. To ensure accuracy he made them act as checks on each other so that some streets were surveyed twice or even three times until discrepancies were resolved. Working ten hours a day it took Whitelaw and his assistants five months to complete the census and produced a total of 172,091, which, with the addition of the garrison (7,000), the Royal Hospital [Kilmainham] (400), the Foundling Hospital (558), Saint Patrick’s Hospital (155), the House of Industry [workhouse] (1,637) and Trinity College (529), came to a grand total of 182,370, considerably short of the previous popular estimate of 300,000.

Arrangement and tabulation

Having spent five months gathering the data it took Whitelaw a further two years of ‘careful supervision’ to tabulate it and a further five before a summary of the work, An essay on the population of Dublin being the result of an actual survey taken in 1798, with great care and precision, and arranged in a manner entirely new, was finally published in 1805. Originally Whitelaw tabulated each house, street by street. From the top to the bottom of the page he listed each house down one side of the street and up the other, including the width of intersecting streets or the length of any blank walls. Across the page each entry was divided into ‘number of house’; ‘number on door’ [not necessarily the same]; the state of repair [‘n’ (new), ‘g’ (good), ‘m’ (middling), ‘b’ (bad) or ‘r’ (ruinous)]; ‘stories high’; ‘upper and middle class’, sub-divided into ‘males’, ‘females’ and ‘total’; ‘servants of ditto’, similarly subdivided; ‘lower class’ [‘the great mass of the labouring poor, working manufacturers, etc. who are not in the service of others’] similarly subdivided; ‘total males’; ‘total females’; ‘grand total’; and ‘name and occupation of proprietor’. For example the twelfth house on the south side of York Street, running from Aungier Street to Stephen’s Green, was numbered ’10’ on the door, was new, four stories high, was occupied by six upper or middle class people (three male, three female), who employed five servants (three male, two female), had no lower class inhabitants, a grand total of eleven persons (six male, five female), and was owned by William Glascock, an attorney. In contrast to this obviously comfortable abode were the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth dwellings (out of a total of twenty-three) on the south side of the Poddle, a small street running between the end of Francis Street and Patrick Street (nowadays the east end of the Coombe), which had no numbers since each was the single floor of a back house in a bad state of repair, reached by a passage between numbers ’14’ and ’15’, but which nevertheless housed twenty-one ‘lower class’ persons (nine males, twelve females). Not surprisingly there were no ‘upper’ or ‘middle class’ inhabitants nor servants. The owner was a Mr Dureen, a baker who probably carried on his trade on the same premises and let the rest in ‘tenements for the poor’.

Because of the bulk of material involved (nearly 500 tables in two folio volumes) it was considered inexpedient for publication and only York Street and the Poddle appear in detailed form in the published Essay as samples of the method employed. The original detailed sheets were lodged in Dublin Castle, from whence they were transferred to the Public Records Office in the Four Courts, where they were destroyed along with countless other irretrievable documents as a result of the fighting that sparked off the Civil War in June 1922. Nevertheless the summary of the material contained in the published Essay is still an invaluable resource, especially for the local historian of Dublin city.

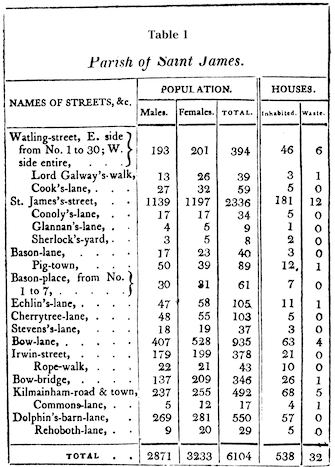

Every street, square, lane, alley, quay, court, yard, etc. (753 to be exact) in the 1798 city is listed individually in its relevant parochial table (numbered I to XXI), indicating its population (male and female) and the number of houses (inhabited and ‘waste’), and also alphabetically in an index at the back with a mention of the next principal adjoining street. This has obvious attractions for the genealogist taxed with the problem of tracing the whereabouts of obscure or long-since-disappeared courts or yards. Whitelaw used Rocque’s marvellously detailed map of forty years before and noted with approval that many of the tiny courts and yards indicated had already disappeared or were uninhabited and used purely for business purposes.

The parish of St James (Table 1.) was dominated by James’s Street, one of the city’s largest, with a population of 2,336 (1,139 male and 1,179 female), inhabiting 181 houses, with twelve waste. Among the parish’s more obscure lanes and alleys was the intriguingly-named Pigtown (off Bason Lane) whose eighty-nine unfortunate residents (fifty male and thirty-nine female) inhabited twelve houses, with one waste. Note that not all of Watling Street is in the parish. Numbers ’31’ to ’42’ on its east side are in the neighbouring parish of St Audeon (VI). Occasionally with larger streets it is necessary to refer to two or even three separate tables to ascertain the population of the entire street.

Population density

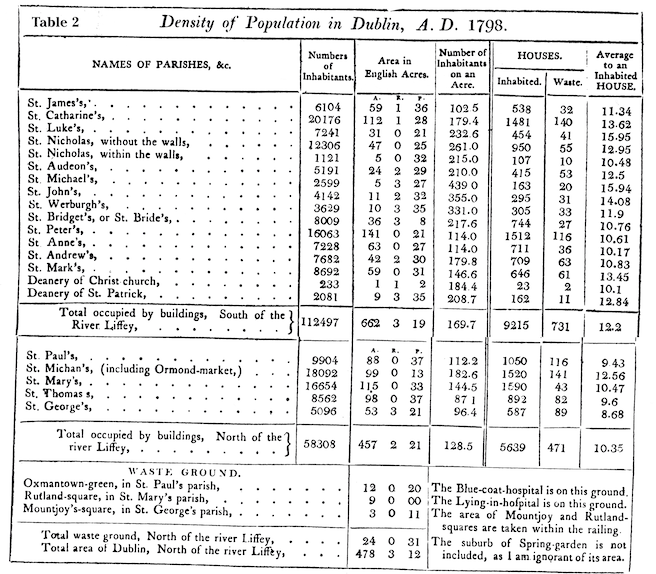

Whitelaw was particularly concerned with the density of population not only to highlight the extent of the squalor of the poorer districts but also to derive mathematical rules of thumb which could be applied to calculate the populations of other comparable European cities. His calculation of population density applied to buildings only and he outlined precise geometric procedures for the exclusion of open spaces such as Stephen’s Green, for example. The parishes within the old walled city were much more densely populated than the newer up-market suburbs—ranging from a claustrophobic 439 persons per acre in St Michael’s (opposite Christchurch) to a more comfortable 87 per acre in St Thomas’s (Sackville Street/Gardiner Street area) (See Table 2.). (By way of comparison, the population density of Dublin in 1981 (according to the Central Statistics Office) was only twenty persons per acre (approximately), but calculated over the whole city, open spaces included.) Whitelaw contended that, provided accurate maps were available, the populations of other cities could be geometrically determined by extrapolating from the actual Dublin experience.

Whitelaw was particularly scathing in his comments on the congested ‘ancient parts’ of the city, for which he blamed high rents and the consequent necessity for tenants to sublet:

I have frequently surprized from ten to sixteen persons, of all ages and sexes, in a room, not fifteen feet square, stretched on a wad of filthy straw, swarming with vermin, and without any covering, save the wretched rags that constituted their wearing apparel. Under such circumstances, it is not extraordinary, that I should have frequently found from thirty to fifty individuals in a house. An intelligent clergyman, of the church of Rome, assured me, that No. 6, Braithwaite-street, some years since, contained one hundred and eight souls. These, however, in 1797, were reduced to 97; and, at the period of this survey, to 56. From a survey taken twice of Plunkett-street, it appeared, that thirty-two contiguous houses contained 917 souls, which gives an average of 28.7 to a house; and the entire Liberty averages from twelve to sixteen persons to each house.

‘Filth and stench inconceivable’

This over-crowded population lived in ‘a degree of filth and stench inconceivable’:

Into the back-yard of each house, frequently not ten feet deep, is flung, from the windows of each apartment, the ordure and other filth of its numerous inhabitant; from whence it is so seldom removed, that I have seen it nearly on a level with the windows of the first floor; and the moisture that, after heavy rains, oozes from this heap, having frequently no sewer to carry it off, runs into the street, by the entry leading to the staircase… When I attempted…to take the population of a ruinous house in Joseph’s-lane, near Castle-market, I was interrupted in my progress, by an inundation of putrid blood, alive with maggots, which had, from an adjacent slaughterhouse, burst the back-door, and filled the hall to the depth of several inches. By the help of a plank, and some stepping-stones, which I procured to the purpose (for the in habitants, without any concern, waded through it), I reached the staircase. It had rained violently, and, from the shattered state of the roof, a torrent of water made its way through every floor, from the garret to the ground. The sallow looks, and filth of the wretches, who crowded round me, indicated their situation, though they seemed insensible to the stench, which I could scarce sustain for a few minutes.

The big picture

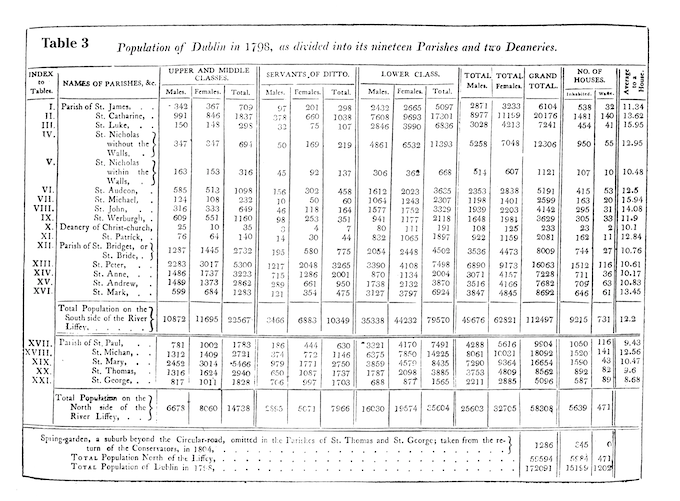

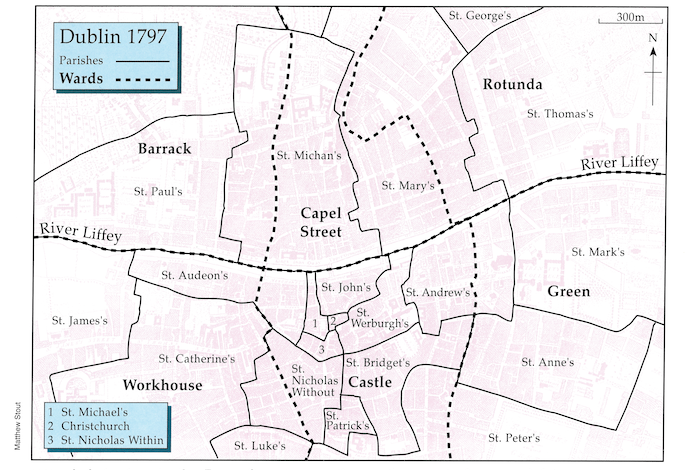

While it is unfortunate that Whitelaw did not apply the class breakdown of the detailed street sheets to the published parochial tables, he did apply it to the grand table of the published Essay (Table 3.). A striking feature is the preponderance of servants—10.6 per cent of the total, with women outnumbering men by a ratio of two to one—an example of how the gentry shaped the occupational profile of the city. The ‘big picture’ of the city’s social profile is best obtained by expressing Whitelaw’s figures as percentages and arranging these into the six wards delineated on Faden’s 1797 map of the city (Table 4.). Clear patterns emerge.

In Dublin city today an allegedly north-side/south-side social dichotomy may be the stuff of humorous anecdote but in fact a west-side/east-side divide conforms more with reality. It was the same in 1798. The new up-market developments to the north-east (the parishes of St Thomas and the newly-created St George) and south-east (St Anne’s and St Peter’s) of the old city had the highest concentration of upper and middle class and servants, with a correspondingly less numerous lower class. These parishes also had the highest ratio of servants to upper and middle class (in St George’s it was almost one to one), suggesting that they were more ‘upper’ than ‘middle’. In marked contrast were the western parishes—St Paul’s and St Michin’s on the north side (either side of Smithfield) and St James’s, St Catherine’s, St Nicholas’s within and St Luke’s (the Liberties) on the south side—which were overwhelmingly proletarian. The parishes in the middle lay somewhere between these extremes but with a much lower ratio of servants than the residential eastern districts, suggesting a more ‘middle’ than ‘upper class’ profile. The picture can be brought into even sharper focus by analysing the spread of businesses (the ‘merchants and traders’ listed in the city’s directories) in relation to population. In the Rotunda and Green wards they are under-represented; over-represented in Capel Street and Castle; and more or less on par in Barrack and Workhouse. In summary, Dublin was divided into three more or less distinct zones spreading either side of the river—up-market residential to the east, middle class/commercial in the middle and proletarian to the west. Twice as many people lived on the south side and at a much higher density, especially in and around the old walled city.

Religious make-up

Originally Whitelaw intended surveying the religion of his respondents but ‘on nearer view…I found it a subject of extreme delicacy: the temper of the times seemed to discourage enquiry’. He did suggest that an approximation could be arrived at discreetly ‘by a little exertion on the part of the Protestant clergy’ visiting their parishioners, totting up the numbers and deducting it from the total. He surveyed the Protestant population of St Catherine’s himself and although this document was not lodged with the Castle and therefore escaped destruction in the Four Courts, neither has it turned up in Church of Ireland records in the Representative Church Body Library. The first proper religious census was carried out in the 1830s and revealed a Protestant (overwhelmingly Church of Ireland) percentage of 27.5. Dickson estimates a 50 per cent Protestant population in the 1730s. An estimate of approximately one third, therefore, seems reasonable for the 1790s.

Motives

Whitelaw produced his census with the sanction of government but at his own expense. Why did he undertake such an onerous task? Partly it was because of the opportunity afforded by the Lord Mayor’s proclamation and partly because of ‘a laudable ambition of being the first to offer to the public, what it has often wished for in vain, an accurate well-arranged census of a considerable capital’. Intellectual vanity was not the only motive, however. Whitelaw was Church of Ireland vicar of the parish of Saint Catherine’s, Dublin’s largest and also one of its poorest, corresponding closely to the Earl of Meath’s Liberty, traditional home of the city’s ‘mob’ (or ‘crowd’). In his introductory essay (subtitled Several observations on the present state of the poorer parts of the city of Dublin) Whitelaw makes several somewhat sarcastic comments on the inactivity of the Protestant clergy. Unlike many of his colleagues, he took a genuine interest in the welfare not only of his parishioners—the bulk of the city’s considerable ‘lower class’ Protestant population resided in Saint Catherine’s—but of the population at large. Using the data he had gathered, Whitelaw relentlessly—and not without considerable wit—batters away at the complacency of the government’s indifference to the plight of the urban poor. He was particularly interested in the provision of education for the Protestant poor and included a survey of parochial schools in the published work.

Availability

Original copies of Whitelaw’s Essay still turn up every now and again in antiquarian book shops but at prices beyond the reach of the average reader. The last facsimile edition was published by Gregg International in 1974 in a collection entitled Slum conditions in London and Dublin in the Pioneers of Demography series edited by Richard Wall. It is still available and your local public library might be persuaded to acquire a copy. Perhaps an Irish publisher might consider publishing a new facsimile edition and make available to a wider public this fascinating insight into the Dublin of 1798.

Tommy Graham is Dublin editor of History Ireland.

Further reading:

J. Whitelaw, An essay on the population of Dublin (Dublin 1805).

R. Wall, Slum conditions in London and Dublin (Farnborough 1974).

D. Dickson, ‘The demographic implications of the growth of Dublin 1650-1850’, in R. Lawton and R. Lee (eds.), Urban population development in western Europe from the later eighteenth to the early twentieth century (Liverpool 1989).

P.Fagan, ‘The Population of Dublin in the eighteenth century with particular reference to the proportions of protestants and catholics’, in Eighteenth Century Ireland 6 (1991).

J. Warburton, J. Whitelaw and R. Walsh, History of the city of Dublin (London 1818).