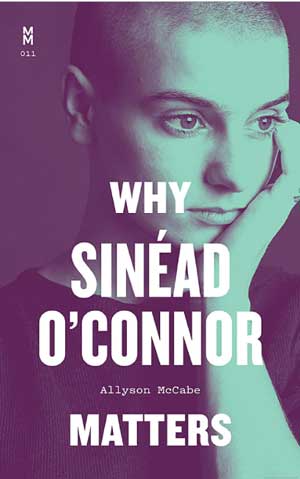

ALLYSON McCABE

University of Texas Press

$24.95

ISBN 9781477325704

Reviewed by Éamon Ó Caoineachan

Éamon Ó Caoineachan is a freelance writer and poet at the University of St Thomas, Houston, Texas.

‘She didn’t just want to sing. She needed to scream’, writes music journalist Allyson McCabe in this biography, published in May, just two months before Sinéad O’Connor’s untimely death in July this year. O’Connor published her memoir, Rememberings, in 2021, and McCabe had the opportunity to interview her on the day of its much-anticipated release. Her engaging interview with O’Connor was intended to be a profile broadcast on National Public Radio in the US, but their stimulating interaction inspired McCabe to write her book detailing the reasons why O’Connor matters. The Irish singer was not ‘the difficult, fragile, and often contradictory mess’ that McCabe and so many of us heard about in the mainstream media. McCabe was stunned to ‘encounter a lucid, insightful, and emotionally honest person’ (BBC Culture). Two years later, McCabe’s 256-page biography is a thorough reflection of O’Connor’s life, which is organised into seventeen parts. It chronicles ‘the triumph and tragedy, sound and story’ of O’Connor’s rise to success, from her critically acclaimed début album The Lion and the Cobra (1987) to the intriguing story behind the lead single ‘Nothing Compares to You’ from her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990). McCabe then provides insight into O’Connor’s perceived downfall in 1992 after the Saturday Night Live controversy when O’Connor infamously tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II while urging viewers to ‘Fight the real enemy!’ The second-last chapter of the book, ‘Hurt People Hurt’, reveals more context to the controversy and is particularly profound as it conveys O’Connor’s traumatic abuse and troubled childhood at the hands of her mother.

McCabe’s thesis functions as a persuasive defence of O’Connor’s life and proposes that the creative and complex genius of her art was a form of activism that transformed music. Today it is common for artists and musicians to use their celebrity status as a platform for protest or social commentary. While O’Connor was certainly not the first artist to use fame as a pulpit, she pioneered incorporating this idea into performance on a scale that was shocking to the conventions of industry standards and mainstream media. O’Connor’s history of staging her art as activism foreshadows the Saturday Night Live protest, as McCabe indicates. In another incident, while singing ‘Mandinka’ during her opening act at the 1989 Grammys, she had Public Enemy’s target logo painted on her head because the recording academy refused to televise the Best Rap Performance. She had also displayed her pride in being both a musician and a mother by wearing her baby son’s onesie around her waist. Music executives warned O’Connor that these antics could destroy her career, since they encompassed the first impression she offered to American audiences, but O’Connor continued to engage in protest performance because she believed in the art of activism. McCabe’s book explains the importance of these episodes and explicitly asserts to readers that it is time for people to reassess O’Connor’s activism and artistic legacy.

Considering that O’Connor’s music was a form of therapy for her and often addressed the trauma she suffered, a minor criticism of McCabe’s analysis is that there is a lack of deep examination of the singer’s lyrics that could also relate to many of O’Connor’s life experiences. Notable examples of these songs include ‘Jackie’, ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘Troy’, to name a few, because they highlight the relationship she had with others and the internal struggle within herself. Other than a wider array of lyrical analysis, McCabe’s attentive examination of O’Connor’s life and music career also serves as a keen exposé of the media manipulation and distortion of O’Connor’s narrative. McCabe clearly advocates for mental health and feminist issues, which are all embedded within O’Connor’s life experiences. This book is tailored to fans who will memorialise her and well suited to historical critics who will write their own articles and books on the late singer. McCabe’s book should be a part of the discussion on how O’Connor will be remembered as a socio-political activist and a significant lyrical artist in Irish music history.

Why Sinéad O’Connor matters draws a distinct comparison to Albert Schopenhauer’s philosophical principle of the three stages of truth as they pertain to O’Connor’s life—‘First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.’ O’Connor’s truth has certainly been ridiculed and violently opposed, yet many of her controversial statements have been gradually accepted over time. Although McCabe’s biography was published prior to O’Connor’s death, this is exactly why people should read it—since it is not solely influenced by the singer’s tragic passing. Overall, the book offers a convincing defence of O’Connor’s radical art that mirrored her radical life, and further presents an empowering perspective of the singer’s truth. McCabe’s final chapter, ‘Truthful Witness’, emphasises why Sinéad O’Connor’s voice matters—because she fiercely fought for the idea that every voice matters.