By Catherine Wright

Until the formation of county councils under the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898, the grand jury was the most important local body in rural Ireland. Originating in medieval times, it was originally responsible for the justice system, but its remit was gradually expanded to include the provision and maintenance of roads, bridges and public buildings such as infirmaries, courthouses and jails. The body also had a range of social and other functions, such as the upkeep of orphaned children, the escort of convicts for transportation, and the production of very early and highly detailed district maps.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the grand jury had a powerful impact on daily life—enforcing law, collecting taxes and spending them, often to the betterment of the grand jury members’ own estates and pockets. Catholics could not legally serve on grand juries until 1793, but in effect thereafter the concentration of land in Protestant hands excluded most Catholics. The grand jury system was increasingly criticised as archaic, corrupt and unrepresentative. Reforms were introduced, such as the employment of county surveyors after 1817, bringing the infrastructural work of the grand juries under the supervision and direction of a corps of professional engineers. Nevertheless, accusations of excesses and inefficiencies persisted.

Wicklow was the last county to be shired by the English Crown, in 1606. After this, the high sheriff of the county called 23 freeholders or landlords to form a grand jury to meet the judge at the spring and summer assizes, which were local court sessions. These panels of prominent landowners were essentially an interconnected network of wealthy families who would dominate local administration until the end of the nineteenth century. The Wicklow juror lists included families such as Parnell, Brabazon, Wingfield, Stratford, La Touche, Acton and Synge, among others.

The records produced by the grand jury are a unique source for local history—documenting the development of infrastructure and social, economic and political life at local and county level. While many grand jury records were destroyed during the revolutionary period, vital collections still survive in county council archives across Ireland, including the collection preserved at Wicklow County Archives, dating from 1790.

The most common surviving records are the grand jury presentments—printed lists of proposed and approved works due to be undertaken, such as proposals and payments for the construction or maintenance of roads, bridges and public buildings. The Wicklow grand jury would also consider and approve payments to public officials and tradesmen for services rendered. Apart from these and other functions such as the upkeep of orphaned children and the accompaniment of prisoners, we find payments for the town crier, the extermination of ‘vermin’ (including otters, magpies and foxes) and other occupations that have long since vanished from public life. These works were funded by means of a county tax or rate known as a cess—spawning the phrase ‘Bad cess to you’. Occupiers (tenants) were taxed rather than the landlords, although in 1870 the first land act relieved smaller tenants of paying the cess.

Grand jury records are also of enormous value to family historians, as the presentment lists usually include the names of officers, contractors and those providing the services. They often specify the work to be done by referencing the property holdings of individuals, connecting families to locations sometimes in tantalising detail: ‘To William Jenkinson … of the Street of Wicklow, between Mr Richard Flanagan’s tavern and Mr Clince’s shop (near the Hibernian Bank); also between Mr Abraham Roger’s house, and the County Courthouse, including the “Mall”’(Wicklow Grand Jury Abstract of Presentments, 1878–9—WWCA/GJ/35). Women also appear more regularly than in many other contemporary records.

Grand jury records often place ancestors in townlands outside the time-frames of the tithe records (1820s/30s) and valuation records (1840s/50s), particularly where parish records have not survived. Local historians find these records useful to draw a fuller picture of local officials and events—using them in conjunction with newspapers, Poor Law Union records, parish registers, gravestones, etc. Another useful feature is that they are usually typescript and when digitised (as in the case of Wicklow Archives) they are highly searchable—for example by surname, place-name or occupation.

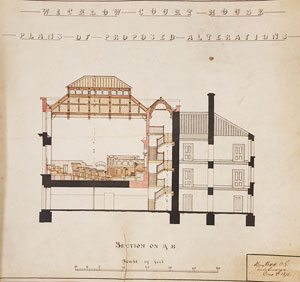

The Wicklow grand jury collection includes beautifully hand-drawn plans for refurbishments of Wicklow courthouse, the meeting-place of the grand jury. The plans are dated 1876 and signed by Henry Brett, county surveyor. Brett was a highly accomplished engineer and former county surveyor for Offaly, Mayo, Waterford and Wicklow until 1880. He assisted Sir Richard Griffith in his ‘primary valuation’ of Ireland and was also engaged in major railway projects. These drawings represent beautifully ornate wood carvings, which survive to this day in the Wicklow courthouse. Indeed, the grand jury would have felt this was fitting for their status and role in society. In 1878 they passed a presentment for the sizeable sum of £450 for the works, which was quite substantial at the time.

Other employees of the Wicklow grand jury were Edward and Mary Storey, who were the governor and matron of Wicklow Gaol. They met when Edward was a turnkey or prison officer, married in 1858 and had a large family. Edward eventually became the governor of Wicklow Gaol in the 1860s—the last governor, in fact, as Wicklow Gaol was downgraded to a bridewell around 1876, when Edward retired. In the Wicklow Grand Jury Payment Books we see details of Edward and Mary’s pension payments. These records assisted in family history research carried out for the descendants of the Storeys by Wicklow County Archives.

The archives of the grand jury are an immensely valuable and perhaps under-used resource for researchers. They provide evidence of the beginning of the county infrastructure as we know it today, with many of our public buildings, roads and bridges built under the aegis of the grand jury. They reference the occupations and home places of ordinary people who may not appear in many other official records of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while also shining a light on local administration and the power of the landed élite.

The Wicklow grand jury collection is digitised on Wicklow.ie. As a participating partner of the Virtual Record Treasury, the Wicklow County Archives has donated copies of the collection to https://virtualtreasury.ie. There you will also see People, power and place: the grand jury system in Ireland, a collaboration between the Virtual Record Treasury and the Local Government Archivists and Records Managers (LGARM).

Catherine Wright is an archivist with Wicklow County Archives and Genealogy Service.