by Benjamin Kline

The relationship between Winston Churchill and Michael Collins has often been characterised as one of mutual respect and rapport which significantly influenced Anglo-Irish relations. Yet, while some form of respect may have developed between these two men, no amount of historical hindsight or sympathetic remembrances should imply that they were anything but adversaries.

The relationship between the two was one of conflict, both in aims and personality. Collins was determined to gain independence for Ireland, within the restrictions dictated by the resources available, while Churchill manoeuvred to retain imperial priorities.

War of Independence (1919-21)

The War of Independence began on 21 January 1919 when the Sinn Fein MPs, who had been returned in the general election of December 1918, formed the first Dáil Eireann and pledged allegiance to the republic proclaimed by the Easter Rising of 1916. In August 1919, the Volunteers, who had formed the army of the republic, took an oath of allegiance to the Dáil and were subsequently refered to as the Irish Republican Army.

The Dáil’s Minister for Defence was Cathal Brugha but it was Michael Collins, Minister for Finance and Director of Intelligence of the Volunteers, who commanded the confidence of the Irish Republican Army. His personal staff, known as ‘The Squad’, attacked the British Intelligence system and played a key role in the events leading up to Bloody Sunday on 21 November 1920.

Churchill, as First Lord of Admiralty in 1915, had borne responsibility for the disastrous attempt to take the Dardanelles and had been forced to resign. Resurrected from his political grave he became Secretary of War and Minister of the Air in January 1919. Thus, both men had ventured on a path which would bring them together as the key figures in Anglo-Irish relations.

In October 1919 Churchill condemned the IRA as ‘a gang of squalid murderers’ who had eluded capture. He supported the police, Black and Tans, and troops who had been forced to fight enemies who could not be easily identified because they could blend into the population without a trace. In particular he was annoyed at the leniency and sympathy shown to hunger strikers who ‘might get out of prison simply for refusing to take their food’. The answer was for England to take a strong stand in order to ‘break up this murder gang’.

The Treaty

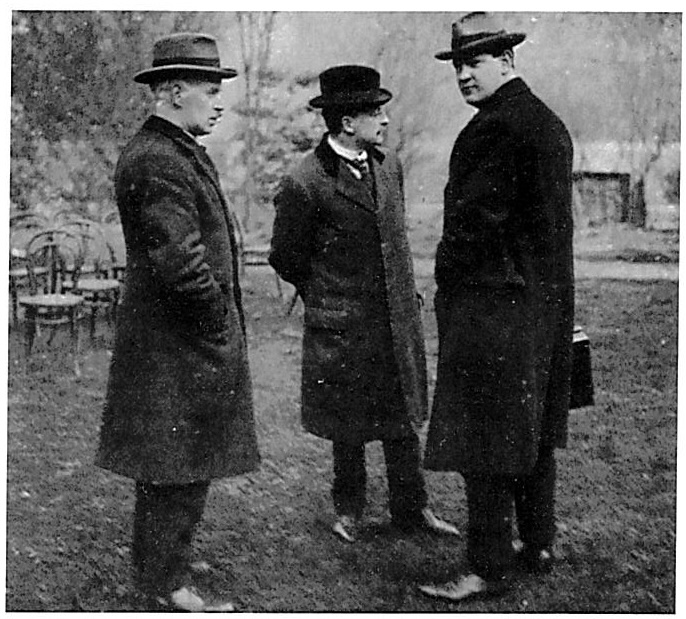

The War of Independence ended with a truce on 11 July 1921. As President of the Irish Republic, Eamon de Valera authorised the members of his government to open negotiations with Britain in October. The basis of the conference was the ‘Gairloch Formula’ proposed by British Prime Minister Lloyd George. According to this formula, the status of a republic, as previously demanded by de Valera, was not acceptable, and instead the Irish delegation — Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, Robert Barton, Eamon Duggan and George Gavan Duffy — was to ascertain ‘how the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire may best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations’. Although Griffith was the top-ranking delegate, Collins was recognised as the de facto leader.

Collins was extremely uncomfortable with being chosen as a delegate. It was not his place nor his field of expertise but it was his duty and he accepted it grudgingly. Batt O’Connor, a close friend, described how Collins bitterly complained that, ‘It was an unheard-of thing that a soldier who had fought in the field should be elected to carry out negotiations. It was de Valera’s job, not his’. Still, Collins was also aware that the IRA was exhausted and that an agreement, even a compromise, was preferable to fighting a ruinous war. Later he argued that the restrictions of the ‘Gairloch Formula’ eliminated any pretence of sustaining the republic:

If we all stood on the recognition of the Irish Republic as a prelude to any conference we could very easily have said so, and there would have been no conference … it was the acceptance of the invitation that formed the compromise.

It has often been charged that as a military man he was prone to interpret political rhetoric too literally. Yet, Robert Barton, who disagreed with the treaty, also came to the same conclusion:

The English refused to recognise us as acting on behalf of the Irish Republic and the fact that we agreed to negotiate at all on any other basis was possibly the primary cause of our downfall. Certainly the first milestone on the road to disaster.

Collins was therefore committed to advancing Irish nationalism rather than establishing a republic.

Churchill’s primary aim was to maintain the British Empire. All that had happened since the Easter Rising of 1916 was irrelevant to this essentially Victorian politician. The negotiations were an opportunity to complete the policy of Home Rule which had been derailed by the outbreak of World War I. He was confident that the Irish people, faced with the generosity and firmness of the British government, would choose to remain within the Empire:

Personally I wished to see the Irish confronted on the one hand with the realisation of all that they had asked for, and of all that Gladstone had striven for, and upon the other with the most unlimited exercise of rough-handed force. I was therefore on the side of those who wished to couple a tremendous onslaught with the fairest offer.

He was willing to surrender local autonomy to the Irish in some form of Dominion status but, if necessary, continue the war to ensure the protection of British interests.

To allow them to come unconditionally would be to admit that the British Empire is an open question … I propose a direct question to them – ‘If you wish to come to a conference on the basis of the integrity of the Empire, come, if not, not’.

A republic was not to be considered nor were the ‘national aspirations’ of the Irish to be a major priority.

While Collins may have appreciated Churchill’s blustery personality during unofficial meetings, he took a critical view of his priorities:

Will sacrifice all for political gain. Studies, I imagine, the detail carefully — thinks about constituents, effect of so and so on them. Inclined to be bombastic. Full of ex-officer jingo or similar outlook. Don’t actually trust him.

Full negotiations began on 11 October in London. As Secretary for the Colonies and Chairman of the Cabinet Commission on Irish affairs, Churchill played a leading role. He and Collins argued about numerous issues, including Britain’s claims to Irish ports for defence purposes, the status of Northern Ireland, and Ireland’s right to neutrality. Collins called Churchill’s demands for the protection of imperial interests ‘coercion’ while Churchill claimed that Collins’ stubborn efforts to ensure Irish autonomy were a ‘refusal to meet us at any point’. In one particular exchange the differences between the British imperialist and the Irish nationalist were made abundantly clear:

Collins: ‘Mr. Churchill, do not you agree that if neutrality were a greater safeguard to you than anything else, it would be a greater value to you than your proposals?’

Churchill: ‘I do not accept that. A completely honest neutrality by Ireland in the last war would have been worse for us. Ireland’s control of her neutrality might be ineffective.’ Collins: ‘All your argument depends on your security. We propose a condition which I contend is a better guarantee of security.’

On the evening of 5 December, Lloyd George confronted Griffith with an ultimatum: the Irish must sign the document or the war would be resumed within three days. Following further discussions between the Irish delegates the Treaty was signed at 2.20 a.m. on 6 December. Southern Ireland was to become a Dominion within the British Commonwealth called the Irish Free State. Churchill viewed the agreement as ‘a great and peculiar manifestation of British genius’ but he recognised that Collins was terribly shaken by the terms he had finally accepted:

Michael Collins rose looking as if he was going to shoot someone, preferably himself. In all my life I have never seen so much passion and suffering in restraint.

Collins interpreted the Treaty as transitional, one step closer to a fully independent Ireland. Churchill was committed to it because it had preserved the Empire and by a sense of obligation -`We have entered into a bargain and we are bound to keep our part of the bargain.’ Still, neither was satisfied by the compromise but they were willing to accept it as the minimum in achieving their opposing goals.

Civil War (1922—23)

On 7 January 1922 the Dáil voted 64-57 in favour of the Treaty, setting off a train of events that eventualy led to civil war less than six months later. De Valera resigned as President, was succeeded by Griffith and a pro-Treaty provisional government was established under the chairmanship of Collins.

While steering the Free State Bill through parliament Churchill described the impending conflict in terms of good against evil:

If you want to see Ireland degenerate into a meaningless welter of lawless chaos and confusion, delay this Bill. If you wish to see increasingly serious bloodshed along the borders of Ulster, delay this Bill … If you want to enable dangerous and extreme men, working out schemes of hatred and subterranean secrecy, to undermine and overturn a government which is faithfully doing its best to keep its word with us and enabling us to keep our word with it, delay this Bill.

This ‘underworld’ of ‘deadly forces’ was not merely a menace to Collins’ government but also to British interests contained in the Treaty. Substantial force was therefore necessary to eliminate it and he lamented that `the Irish have a genius for conspiracy rather than for government’.

Churchill readily offered Collins military equipment and encouragement in an effort to bolster what he believed to be a half-hearted attempt by the provisional government to face down their former comrades. On 12 April 1922 he informed Collins that the British government expected the Free State to maintain order and enforce the terms of the Treaty:

It is obvious that in the long run the government, however patient, must assert itself or perish and be replaced by some other form of control. Surely the moment will come when you can broadly and boldly appeal not to any clique, sect or faction, but to the Irish nation as a whole.

By May Churchill’s confidence in Collins had been further shaken. He informed the British cabinet that the Free State was on the verge of sliding ‘into an accommodation with the republicans’. He could no longer trust Collins to stand firm against the ‘irregulars, hooligans [and] bolsheviks’ of the IRA. Therefore, in the case of a republic being declared ‘we shall lose confidence in the provisional government’ and ‘that is war’. For Collins, the split within the IRA was a personal tragedy. He was not disturbed by the possibility of losing the friendship of de Valera or of anti-Treaty politicians but of alienating his former comrades in the army. Those same ‘dangerous and extreme men’ whom Churchill castigated were once Collins’ friends and allies.

In his writings and comments it is clear that Collins was endeavouring to avoid a split which would retard the progress he felt had been achieved in the pursuit of Irish independence:

The humiliating fact has been brought home to us that our country is now in a more lawless and chaotic state than it was during the Black and Tan regime. Could there be a more staggering blow to our national pride, and our national hopes?

Ireland required a united struggle by its people to transform the limited political gains of the Treaty into the freedoms he had sought since entering the Post Office on O’Connell Street that memorable Easter Monday in 1916. In May 1922 Collins, in reply to a letter sent by Paddy Daly , a former close associate in the IRA, expressed his faith in the political course he had chosen:

Believe me the Treaty gives us the one opportunity we may ever get in our history for going forward to our ideal of a free independent Ireland.

The Four Courts

The Four Courts, the centre of the Irish judiciary, was seized by the 3rd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA on 14 April 1922. This occupation had not been authorised by the IRA Executive but over the next two months many republicans enlisted with the occupying garrison. Initially, no attempt was made by the provisional government to dislodge them.

Churchill viewed the Four Courts as a symbol of the provisional government’s capacity (or incapacity) to govern. On 26 June, speaking in the Commons, he announced an ultimatum. Unless the provisional government brought the occupation of the Four Courts to a speedy end, His Majesty’s Government would regard the Treaty as having been violated and would resume ‘full liberty of action’.

When he heard of Churchill’s speech Collins angrily declared, ‘Let Churchill come over and do his own dirty work.’ To him the Four Courts’ leaders were not mutineers but former and, he hoped, future allies; allies Ireland would need to exploit the provisions of the Treaty and the constitution which he expected one day would bring peace and unification. Thus, a priority of his policy was to avoid deepening the divisions in the country by ‘striking the first blow against republicans’. Furthermore, the ultimatum brought into question the autonomy of the Free State government by creating the impression of compulsion by the British. However, delaying tactics were no longer feasible and in a specially convened meeting the decision was taken to move against the Four Courts. The attack began on 28 June and lasted two days. It resulted in 65 killed, 270 wounded and 25 buildings destroyed. Churchill’s congratulations were hardly welcomed by a despondent Collins:

Now all is changed. Ireland will be mistress in her own house, and we over here [in Britain] are in a position to safeguard your Treaty rights and further your legitimate interests effectually.

Northern Ireland

On the northern question, Churchill preferred diplomatic measures. He was not opposed to the principle of Irish unity —’That is our policy’. But such an event could occur only when Northern Ireland chose to end its union with Britain. Until such an occurrence, the British government would recognise its ‘obligation for the defence of Ulster.’ He was convinced that the IRA was the primary cause of the difficulties in Northern Ireland and ‘the continuous effort by extreme partisans of the south, to break down the Northern government and force Ulster against her will to come under the rule of Dublin’.

During the Treaty negotiations Collins had argued that the six county state represented an artificial partition:

South and east Down, south Armagh, Fermanagh and Tyrone, will not come in Northern Ireland and it is unfair to ask them to come in it. We are prepared to face the problem itself – not your definition of it.

In later comments he would regret the clause which surrendered the north-east to British rule and there is evidence that his government was implicated in cross-border hostilities.

Loyalist attacks

Collins’ primary concern was to protect nationalists against loyalist attacks. He warned Churchill that such actions would provoke a backlash which he would be unable to control:

I must point out to you that the situation in the Six Counties could not be graver. If these offensive not protective measures are taken against our people it will fan a flame of indignation and passion amongst the people of the whole country, and I cannot be responsible for the awful consequences that must ensue.

Churchill attempted to downplay events and urged Collins to take a more moderate stance:

From the imperial point of view there is nothing we should like better than to see north and south join hands in an all-Ireland assembly without prejudice to the existing rights of either. Such ideas would be vehemently denounced in many quarters at the moment, but events in the history of nations sometimes move very quickly. The Union of South Africa, for instance, was achieved on a wave of impulse. The prize is so great that other things should be subordinated to gaining it. The bulk of people are slow to take in what is happening, and prejudices die hard. Plain folk must have time to take things in and adjust their minds to what has happened. Even a month or two may produce enormous changes in public opinion.

Collins’ reply was diplomatic but could not hide the fact that, unlike Churchill, he found it impossible to view the Northern Ireland issue as anything else than a harbinger of future turmoil:

I appreciate very much your observations on the north-eastern situation and your suggestions for the achievement of Irish unity. Believe me this all-important question is never far removed from my thought … We must seek for a better and more permanent solution, and one which will not be so liable to perpetuate bitter memories amongst neighbours.

Churchill managed to bring Collins and the Ulster Unionist leader, Sir James Craig, together to forge an agreement on the northern problem. Two accords were eventually signed but neither was effective. Catholics in the northern state remained victims of institutional discrimination while IRA attacks on Northern Ireland, from both internal and cross-border bases, continued unabated.

Collins and Churchill had differing opinions for the failure of the Collins-Craig agreements. Collins blamed those in the north who wished to see the return of British rule to all of Ireland and the policies of the Northern Ireland government. In response to a letter from Craig he placed responsibility for the violence squarely on the shoulders of Unionist politicians who had turned a blind eye to the actions of loyalist extremists.

Your letter has apparently been drafted with a view of keeping attention off the daily practice of atrocities and murders which continue uninterrupted in the seat of your government. There is not space here to detail the abominations that have taken place in Belfast since the signing of our pact, and I understand your desire to draw the attention of civilisation away from them.

Churchill was responsible for placating Craig as well as Collins and consequently took a more objective view of the conflict. This was a matter for diplomacy, one which could be worked out if both parties remained persistent. He never admitted that the Collins-Craig agreements had failed but instead claimed that they had yet to be fully implemented. In numerous letters he encouraged Collins and Craig to enforce the terms of their agreement and use his offices to organise further meetings. In April 1922 he wrote to Collins to assure him that Craig ‘has made a very great effort to fulfil the agreement in the letter and in the spirit, and that he is continuously and will continue in that direction’. In July, after the Four Courts had been recaptured by National Army troops, he advised Collins that the defeat of the republicans presented an ideal opportunity to renew efforts to solve the Ulster problem:

I wish to keep the ground clear in hopes of a general return at the right moment to the governing idea of the Collins-Craig pact … I think you should turn over in your mind what would be the greatest offer the south could make for northern co-operation.

Churchill, trained as a politician and diplomat, was inclined to interpret the problem as a matter between two states which, over time, could be reconciled through negotiations, with Britain acting as mediator. Collins, however, was more concerned about the plight of northern nationalists and in particular he opposed a bill which abolished proportional representation. He warned Churchill that such legislation by the Unionist government was tantamount to advocating a Protestant monopoly of political power:

Not merely is it intended to oust Catholic and nationalist people of the six counties from their rightful share in local administration, but is beyond question intended to paint the counties of Tyrone and Fermanagh with a deep orange tint.

(COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND).

The future of Ireland

Collins desperately wanted to reconcile his old comrades and end the conflict which had divided nationalist Ireland. He had always regretted the terms of the Treaty and in particular the creation of Northern Ireland. In February 1922 he expressed his determination to end partition, ‘It would be far better to fix our minds for a time on a united Ireland, for this course will not leave minorities which it would be impossible to govern’. In this spirit Collins worked to reconcile the anti-Treaty members of the IRA. On 20 May a compact was signed between himself and de Valera concerning the approaching election. Pro and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin TDs were to be returned in the same proportion as in the previous Dáil – 64 to 57.

Churchill was determined to prevent any agreement with republicanism and declared that a republic was ‘a form of Government in Ireland which the British Empire can in no circumstances whatever tolerate or agree to’. He received news of the impending agreement a few days before its signing and immediately wrote to Collins:

I think I had better let you know at once that any such arrangement would be received with world-wide ridicule and reprobation … It would not invest the Provisional Government with any title to sit in the name of the Irish nation. It would be an outrage upon democratic principles and would be universally so denounced.

Collins ignored Churchill.

In May 1922, Collins visited London and attended a Westminster debate in which Churchill criticised the Collins-de Valera Pact. Immediately afterwards they met privately. Churchill mentioned to him that if any part of the Irish Republican Army, either pro- or anti-Treaty, invaded northern soil, Britain would retaliate. Collins’ parting remarks were a premonition of his own death and the hope he retained for Ireland’s future:

I shall not last long; my life is forfeit, but I shall do my best. After I am gone it will be easier for others. You will find they will be able to do more than I can do.

Conclusion

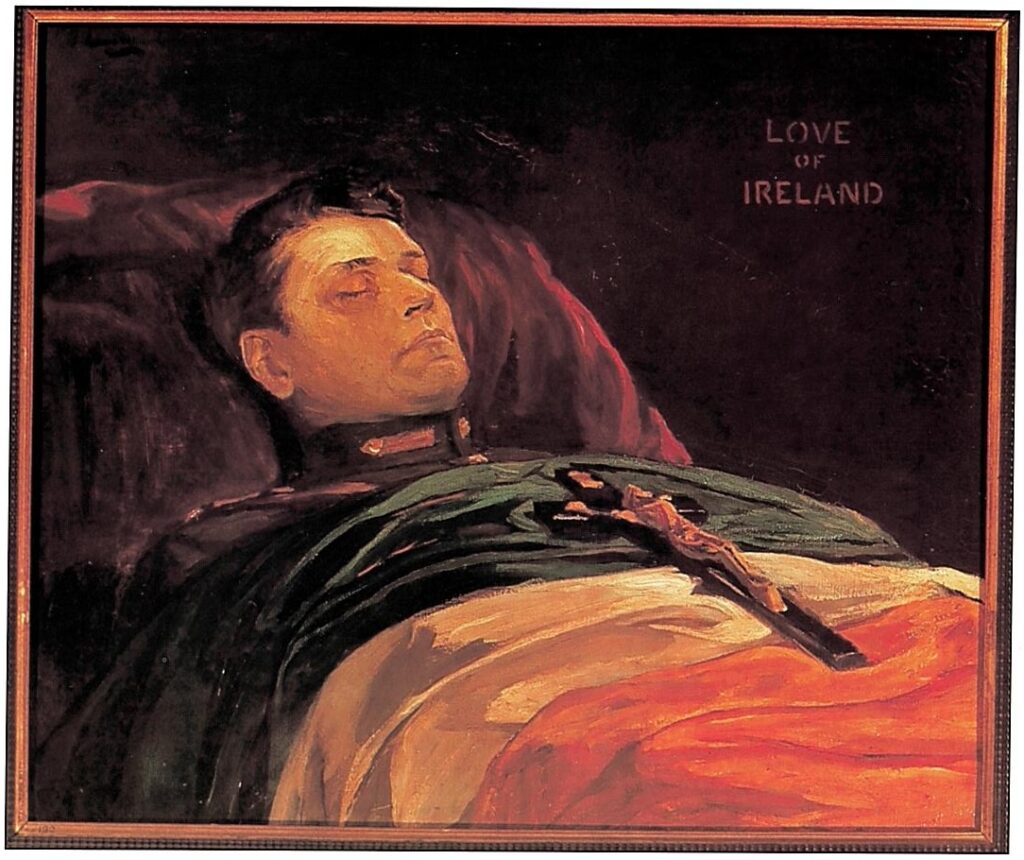

Michael Collins was killed in an IRA ambush at Béal na mBláth, County Cork, on 22 August 1922. Seven years later, Churchill would pay homage to his one time military enemy and political ally. He admired Collins but evidently continued to be ignorant of the ideals which had driven and permanently separated the two men:

He was an Irish patriot, true and fearless. His narrow upbringing and his whole life had filled him with hatred for England. His hands had touched directly the springs of terrible deeds. We hunted him for his life, and he had slipped half a dozen times through steel claws. But now he had no hatred of England.

Churchill and Collins were never partners nor did they share a common affection for England. Winston Churchill, the consummate politician, manoeuvred to maintain a disintegrating British Empire, while Michael Collins, the military man, was forced to navigate the treacherous waters of diplomacy. Collins had never viewed the existing situation in 1922, which he had helped create, as Ireland’s final fate. It was a short-term halt on the road to full independence. Churchill’s goal was to stall, if not stop, the rupture in the British empire. One was a visionary and the other an opponent of change but neither accomplished their dreams. However, together they forged the future of Ireland.

Benjamin Kline is a history professor at Wheelock College, Boston.

Further reading:

R.R. James (ed.), Churchill Speaks: Collected Speeches in Peace and War (Leicester 1980).

T.P. Coogan, Michael Collins: A Biography (London 1990).

M. Bromage, Churchill and Ireland (Notre Dame 1964).

M. Forester, Michael Collins: The Lost Leader (London 1971).