By Padraig Yeates

Twenty-five years after the official ending of the Troubles, Northern Ireland remains a deeply divided society. Even the title of the ‘peace agreement’ is contested, variously called the Good Friday, Belfast and Belfast/Good Friday Agreement.

We have had two parallel processes in place. One is a suite of programmes funded by the Irish and British governments that facilitate reconciliation between communities in the North and between North and South. The other has been the painfully protracted process, also publicly funded, by which victims and survivors seek truth and justice through the courts for cases reaching back over 50 years to the start of the Troubles.

The British government is now planning to deny victims access to the courts with the Legacy Act. Legal challenges are already under way which may well end up in Europe.

We need a radically different approach. The Irish and British governments must revisit the Stormont House Agreement, of which they are signatories, and particularly its most successful section, the Independent Commission on Information Retrieval (ICIR), which has retrieved the remains of most of the victims ‘disappeared’ during the Troubles.

For many victims and for society at large, information-sharing through mediation is a far more effective way of reaching the truth than litigation. Meanwhile, the criminal justice system must remain the primary means of addressing the legacy of the Troubles for those victims and survivors who so choose.

Unfortunately, it is only when people find themselves in court that they discover how inefficient, expensive, time-consuming, emotionally draining and unsuited to retrieving reliable testimony it is. If they are giving evidence, particularly if they are trying to recall the chaos in which others were killed and seriously injured decades ago, they become acutely aware of how imperfect the system is and how difficult their own situation can become, especially if their recollection conflicts with the prevailing narrative of one or more of the legal teams.

On 9 and 10 August 1971 I was in the Whiterock and Ballymurphy areas of Belfast and consequently found myself providing evidence at the inquests into the deaths of the ten people killed there on those dates. At the time I was helping with Workers’ Radio. Our location on the Black Mountain let us relay messages across the city. Tuning in was one of the few ways by which people stranded in various locations around Belfast could keep in touch with family and friends. News bulletins were a mixture of rumour, hard information and propaganda. The selection of music was determined by the dozen or so LPs we had to hand. My cousin Sylvest was the song in most demand.

On Monday 9 August we stopped broadcasting as it grew dark because of the increased risk of British Army incursions. There was escalating gunfire coming from the direction of the interface with the loyalist Springmartin estate higher up the mountain. Eddie McDonnell (now deceased), who was a member of the local Republican Club, and I made our way to the home of a member of the Official IRA in search of information. Men were queuing outside waiting for weapons to defend the area, not at that stage from the British Army but from ‘UVF’ gunmen. (In fact, the ‘UVF’ gunmen concerned were members of the Springmartin Defence Association, later a branch of the Ulster Defence Association.) In 2019 I met one of them and he told me that they took out their weapons after three local teenagers had been shot and wounded ‘by a gunman from Ballymurphy’ while they were helping a Protestant family leave Springfield Park. Similar evacuations were taking place across Belfast that day, but fortunately did not escalate into a full-scale gun battle.

People on both sides were driven by communal fear. In loyalist areas leaflets were circulating, claiming that internment had been introduced to prevent a Fenian insurrection. Nationalists feared that they were going to experience a repeat of the pogroms of the 1920s, 1930s and, of course, August 1969. Gathering darkness did nothing to alleviate the growing belief that the ‘UVF’ was coming to slaughter people in their beds. The internment arrests that morning were seen as a deliberate move to leave Catholic areas defenceless.

It was soon clear that no guns were coming to augment the handful already in the area, so Eddie and I went down to the NICRA (Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association) office in Marquis Street to tell them of the escalating sectarian gun battle and the need for troops to contain it. NICRA rang a Whitehall ‘hot line’ only to be told to call Thieppeville, HQ of the 39th Brigade, in Lisburn. The British Army was now running the show. Initially these calls were dismissed but eventually the Army conceded that its own units were reporting escalating ‘sectarian gunfire’ in the area and someone was being sent up.

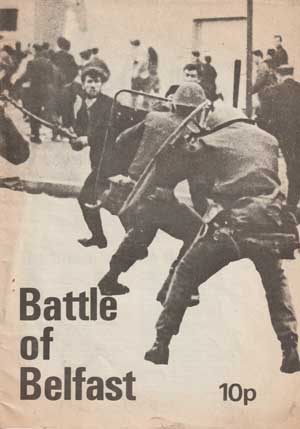

What followed has become known as the Ballymurphy massacre, and if you ask most people who was responsible they will say the Parachute Regiment. I had written a pamphlet, Battle of Belfast, in the immediate aftermath of internment and it was on that basis that I received a summons to give evidence at the inquest in September 2019. I was reluctant to do so because my recollections were extremely hazy after almost 50 years. I didn’t know the area well and much of what happened occurred in darkness, as the public lighting had been destroyed. Moreover, Eddie and I spent nearly two hours either in the NICRA office or travelling there and back when some of the fatal shootings took place.

I notified the coroner of my reluctance to give evidence, but I was summonsed anyway. My recollections did not suit either of the legal teams. A barrister representing the families of two victims questioned me closely about my movements and sought to have me cited for contempt when I refused to identify the Springmartin Defence Association member who had earlier told me that the British Army had given them some rifles for self-defence after earlier gun battles with the Provos. I promised the coroner that I would endeavour to ask the individual concerned to give evidence, and she decided to adopt what was a more positive route out of this legal impasse than finding me in contempt. I was unsuccessful in that endeavour. A barrister representing the British government had only one question: was I at the time a member of the Official IRA? I said that I was. He thanked me and sat down. That was it.

In her findings the coroner described me as giving my evidence ‘candidly’. To what extent it influenced her findings I have no idea. But returning to the question of dominant narratives, a number of points did emerge from the coroner’s findings that have been largely ignored. The first is that the Paras were not the only soldiers sent to Ballymurphy that night; so too were members of the Queen’s Regiment and various specialist units, as is clear from soldiers’ depositions to the court and battalion records.

A soldier who served several terms of duty in Northern Ireland, including one during the introduction of Internment, told me earlier this year that word on the Army grapevine in 1971 was that the Queen’s Regiment did most of the shooting. The only soldier who was clearly identified at the inquest as having shot a civilian was ‘M3’, a member of the Royal Engineers. He claimed that he was clearing a barricade and only fired in self-defence at a rioter who threw a petrol bomb at the cab of the bulldozer he was driving. The petrol-bomber missed M3, who missed the petrol-bomber but killed 31-year-old Edward Doherty, a father of four, further down the road.

Following the inquest, M3’s conduct was referred to the DPPS (Director of the Public Prosecution Service) by the coroner for failing to undertake an adequate safety audit before discharging his firearm, and for failing to give the three mandatory verbal warnings to the petrol-bomber. M3 had ended up in hospital himself with head injuries sustained while clearing the barricades.

The coroner concluded that soldiers killed eight civilians in Ballymurphy and probably a ninth, while John McKerr, a local resident and former soldier, was shot by persons unknown. Unfortunately, reconciliation of the facts requires a degree of honesty and space for reflection rarely achieved in a courtroom, yet without reconciliation on the facts how do we achieve it on anything else? This is especially the case where the personal stakes for witnesses can be high, testimony is fiercely contested and is sometimes reconstructed by witnesses themselves for many reasons, including the vindication of group narratives.

The main reason why I answered the summons was that some other former paramilitaries indicated that they would testify if I did. They changed their minds after seeing my experience in the witness-box.

We need something better than the Legacy Act.

Padraig Yeates is the secretary of the Truth Recovery Process (CLG), www.truthrecoveryprocess.ie.