By John O’Brien

Lawn tennis exploded onto the Irish social scene in the summer of 1874, just weeks after the first advertisements for lawn tennis equipment appeared in English newspapers. As the 1875 season approached, Lawrence’s ‘depot for manly sports’ on Sackville Street began to advertise tennis equipment in the Irish Times. From the end of the 1875 season onwards, Lawrence’s dropped the use of the word ‘manly’ in reference to its entire sports department. It seems evident that lawn tennis was immediately recognised as a sport for both sexes, and retailers needed to rebrand quickly.

Irish women enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with tennis during these formative years, a relationship that was critical in shaping the development of the game in Ireland. The ascent of tennis in the late 1870s and throughout the 1880s was perhaps even more pronounced in Ireland than it was in Britain. The early game appealed particularly to the aristocracy and landed gentry, who held social gatherings centred on courts constructed on their private demesnes. These parties quickly became central to the social calendar of the élite classes, facilitating both the conveyance of wealth and the prospect of romance. In 1879 the Freeman’s Journal remarked that ‘no well-connected and properly brought up young lady or gentleman moving in respectable society would dare to confess herself or himself unacquainted with the mysteries of the fashionable game’.

EMANCIPATING IMPACT

The emancipating impact of tennis was felt by women throughout the country, and increasingly by those from outside the élite classes. A Westmeath Independent article declared that the women of Athlone ‘look upon the game [of tennis] as one especially designed by Providence for their benefit’. In rural towns, lawn tennis clubs were invariably appended to existing clubs associated with other sports. These previously male-dominated clubs benefited financially from the innovation of offering recreational opportunity to women. In Dublin, however, tennis generally served to replace pre-existing recreational outlets. In 1877 the ‘popular game of lawn tennis’ was advertised as an imminent appendage to the attractions of Rathmines Skating Rink, an established social gathering space for both sexes. The need for fashionable recreational pursuits was critical in supporting the marketability of new real estate in fledgling suburbs. This resulted in the establishment of dozens of exclusive tennis clubs, as well-heeled Dublin families fled from an overcrowded city centre. An article in the 1889 Irish Society magazine provides intriguing glimpses into how middle-class Rathmines expected romantic outcomes from tennis and used the clubs to help create a simulacrum of elevated status:

‘We would like to impress … that chivalry is not yet supposed to be dead amongst the Irish race. The nineteenth century may not afford such scope for deeds of valour as did the fourteenth, but it affords ample opportunities of discharging courtesy and gallantry. These gentlemanly characteristics seem somewhat at a discount amongst the Ormonde members, as ladies are permitted to walk home unaccompanied. It would seem all Ormonde men are engaged, and therefore we fancy it would be out of place to escort other than their affianced. Men of the Ormonde Club, is this not so?’

The lack of female participation in nineteenth-century sports is generally attributed to the ‘separate spheres’ concept, whereby women occupied the private environment of the home while leisure sat firmly within the public, masculine sphere. However, tennis’s combination of physical exercise in fashionable clothing, the mixed doubles format and the privacy of the clubs created an environment where spheres could overlap. While some sources suggest that Victorian-era sportswomen were likely to have participated passively, Catriona Parratt’s survey of contemporary sources suggests that women ‘competed, excelled, and exhilarated in the sensuality of physical exertion and the mastery of bodily skill’.

Parratt’s view would certainly appear to have been true of Ireland. Indeed, both ladies’ singles and mixed doubles events were contested in the inaugural year of the hugely popular Irish Championships, which were first held at Fitzwilliam in June 1879. These events followed Fitzwilliam’s own club championship, where the ladies’ singles final was contested ‘with great skill’ in front of a ‘large and distinguished company’. Ireland led the world in hosting an open ladies’ competition, with Wimbledon not following suit until 1884. By 1892, Irish ladies Mabel Cahill and Lena Price, graduates of the aristocratic tennis party scene, had between them secured a Wimbledon singles title and two successive clean sweeps of all the ladies’ trophies in the US Open.

RESTRAINT

Nonetheless, restraint prevailed. Early images of Irish élite tournaments and social gatherings reveal women’s clothing as being exceptionally restrictive, with ankle-length dresses, full-length sleeves, decorated headwear and rigid shoes. The original 1879 ladies’ singles championship was held at the Fitzwilliam club’s private grounds rather than on Fitzwilliam Square. In 1880 The Field reported that the ladies’ competition continued to suffer from the continued ‘unwillingness of the fair sex to play in public’, with admission to Fitzwilliam’s grounds restricted to members. This was in contrast to the mixed tournament, which was played in Fitzwilliam Square. At least in Dublin, participating women seem to have quickly overcome these reservations. Indeed, Pastime reported crowds of over 6,000 attending the ladies’ championships on Fitzwilliam Square in 1884, although evidence gathered by Tom Hunt on inter-club contests in Westmeath would suggest that women’s willingness to expose their abilities to public scrutiny had not spread to rural towns by 1888.

Ireland was unusual in that the Victorian sporting revolution confronted a well-organised domestic sporting initiative, the newly founded Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It seems clear, however, that the GAA’s ambitions were confined to the battle for Irish masculinity, and women were largely ignored. At the inaugural meeting of the GAA in 1884, a letter was read out from Archbishop Croke describing ‘foreign and fantastic field sports [such] as lawn tennis’ as ‘effeminate follies’ played by ‘degenerate dandies’. Perhaps owing to its immense popularity with women, its perception as a recreational rather than a competitive game and the existence of a mixed doubles format, tennis was not seen as part of the fight for sporting dominance that was to play out in subsequent years. Despite topping Croke’s list, tennis therefore escaped the GAA’s 1886 ban on ‘foreign’ sports.

DECLINE AND REVIVAL

Regardless, the game in Ireland went into near-terminal decline after its early-1890s zenith. Already in 1890 Pastime opined damningly that tennis was becoming ‘popular’ rather than ‘fashionable’. The decline has been attributed to a number of factors, including the ‘crumbling power of the game’s key demographic for patronage’. The landed classes took to more exclusive pastimes in which social segregation and privacy remained possible. As early as 1885, Kildare socialite Maria La Touche wrote of the ‘present Irish fashion of playing rounders instead of tennis at parties’. Perhaps an accentuating factor was that the Dublin Lawn Tennis Council did not hold its first ladies’ league until 1910, eight years after its first men’s league. This seems strange, given the dominance of Irish women on the international tennis circuit in the early 1890s and the growing willingness of women to compete under the public gaze. The delay may be due to the lack of a national governing body for the sport until 1908 and the limited influence that women are likely to have had in the initial inter-club discussions needed to facilitate competition.

Tennis experienced a revival after the Great War, as the world went pleasure-mad. After the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, the Irish governing body resolved ‘that the Irish Lawn Tennis Association (ILTA) be established on independent lines similar to the Governing Associations in the Dominions’. A key individual in the ILTA was honorary secretary Harry Maunsell, who was supportive of women’s participation in tennis. Maunsell ‘pursued a local agenda of increasing the appeal of tennis to a wider audience and encouraging the participation of children in the sport’. In 1936 he sought to recognise female achievers at a time when Irish commemorative activity was keenly focused on nationalist male heroes by publishing a letter requesting that ‘Mabel Cahill, or her representatives, kindly communicate with the ILTA, relative to a gold medallion which can be claimed on her behalf’.

NEW CLUBS

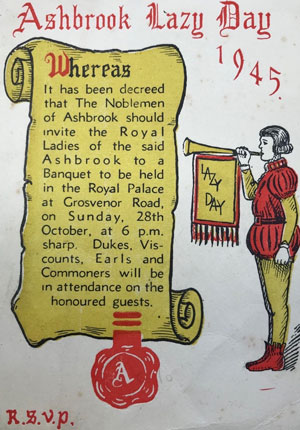

A number of new clubs emerged in the 1920s, with photographs evidencing balanced gender representation and clothing somewhat more suitable for physical exercise. The early minute-books of Ashbrook Lawn Tennis Club (then in Terenure but now in Rathgar) show that its 1929 committee included six women. There is no evidence of any tension over gender balance in the use of the nascent club’s resources; indeed, positive discrimination is evident in subscription rates, where the 1931 ladies’ rate was £1-1s., versus £1-10s. for men. Gendered roles are nevertheless evident in the existence of a ladies’ committee whose remit related to hospitality. Efforts put into hospitality were rewarded in Ashbrook from the 1930s through the 1950s with the annual occurrence of a quaint ‘Lazy Day’ on which men took over the catering arrangements and entertained the ladies.

Irish newspaper commentary on the 1924 Aonach Tailteann suggests a positive attitude towards women’s tennis in the early years of the Free State. Newspapers describe worldwide interest in Tennis Tailteann, expecting it to be one of the most successful of the sports on display. Alongside a competitive ladies’ singles draw, fourteen teams contested the ladies’ doubles, while 26 teams contested the mixed doubles. At the inaugural day, however, ladies were relegated to playing on peripheral courts, even though the centre court was unoccupied by men’s matches until 2pm, and newspapers reported poor attendance.

Tennis was enthusiastically embraced by Irish women seeking relief from the restrictions of their private-sphere lives. Such was the extent of its appeal on the island that for a brief period Ireland’s aristocratic women dominated global competitive tennis. While the opportunity to contribute to the vitality of mixed-gender clubs and to compete physically on court were undoubtedly emancipating, tennis-loving Irish women have also had to compete with all-too-familiar challenges, some of which continue to this day.

John O’Brien is the former chairman of Stratford LTC in Rathmines and compiled a centenary publication for Ashbrook LTC in 2022.

Further reading

S.J. Eaves & R.J. Lake, ‘The forgotten powerhouse: analysing the brief rise to prominence of lawn tennis in Ireland in the late nineteenth century’, International Journal of the History of Sport 36 (11) (2019), 959–81.

T. Higgins, The history of Irish tennis (3 vols) (Sligo, 2006).

T. Hunt, ‘Women and sport in Victorian Westmeath’, Irish Economic and Social History 34 (1) (2007), 29–46.

C.M. Parratt, ‘Athletic womanhood: exploring sources for female sport in Victorian and Edwardian England’, Journal of Sport History 16 (2) (1989), 140–57.