By Brian Griffin

Scholars such as Eileen Reilly, Caitriona Clear, Niamh Gallaher and Fionnuala Walsh have documented the important contribution that Irish women made towards the United Kingdom’s war effort during the First World War. One of the main topics which they have explored is women’s involvement in supporting British servicemen, either in Voluntary Aid Detachments, by raising money for various charities that aided servicemen and their families, or by providing comforts such as tobacco, cigarettes, socks, scarves and mittens to wounded soldiers in Irish hospitals and to Irish servicemen who were serving overseas. Less well known is the role of football in Irish women’s war-related support activities.

Although association football did not feature so prominently in Irish society as it did in Britain, nevertheless it was popular on a regional level, with Dublin city, some of the larger Munster towns and, above all, Belfast and some of the larger towns in Ulster proving particularly receptive to the sport. Unlike the situation in England, where competitive football was discontinued after the 1914–15 season, competitive football continued to be played in Ireland throughout the war, albeit in two new regional leagues for the highest-level clubs rather than a single all-Ireland league from the 1915–16 season onwards—the Belfast and District League and a slightly expanded Leinster League. Football provided a welcome wartime diversion for civilian and servicemen supporters. This was particularly the case in Ulster, where war industries were more numerous than elsewhere in Ireland and where large numbers of locally recruited soldiers (many of them formerly urban workers, who constituted football’s main support base) spent time in training before they were sent to the front. These supporters became a lucrative source for women fund-raisers during the war.

LADIES’ FOOTBALLERS’ GUILD

In November 1916 the Belfast newspaper Ireland’s Saturday Night published a letter written by several soldiers of the Royal Irish Rifles who were ‘Somewhere Abroad’, in which they expressed their gratitude to the Ladies’ Footballers’ Guild for the ‘little comforts’ which the guild had sent to soldiers serving overseas. The guild, which had been formed at some point earlier in the 1916–17 football season, was directed by Diana Scott, wife of the secretary of Distillery Football Club, and Henrietta Ireton, a bookkeeper who worked in Belfast. The soldiers reported admiringly of the guild’s two principals that ‘Their fame is spreading amongst the Belfast boys out this way, and we all greatly appreciate the work which these two ladies from Ulster are doing for the comfort of the troops with the Expeditionary Forces all over the world’. Scott, Ireton and other female volunteers organised collections amongst the spectators at football matches, the proceeds of which were used to pay for parcels of ‘eatables and smokes’, as well as footballs and newspapers—especially Ireland’s Saturday Night, a favourite with Belfast football fans serving in the British Army and Royal Navy—to be posted to servicemen. Other funds for this purpose were raised at a football match at Grosvenor Park, Distillery’s home ground, which was organised by Scott in May 1917 between soldiers of the Scottish Command Depot and a ‘Distillery Selected’ team (which actually comprised players from Belfast Celtic, Linfield, Glentoran and Distillery), and a guild-organised ‘Grand Whist Drive and Dance’ in the Carleton restaurant in October 1917. The guild also funded entertainments for wounded soldiers from the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) hospital and troops based at the Randalstown military camp.

By October 1917 Scott and Ireton had parted company, with Ireton heading a separate Linfield Ladies’ Guild, which organised collections amongst fans attending matches at Linfield’s Windsor Park ground. Ireton was the first member of the Linfield Ladies’ Guild to get involved in these collections, which paid for parcels to be sent to servicemen overseas as well as paying for entertainments for wounded soldiers and sailors from Belfast’s hospitals. By January 1918 she was being assisted by sixteen other women. These included the guild’s treasurer, Maude Clarke, a handkerchief boxer.

WOMEN FOOTBALLERS

Another way in which women in Ulster supported the war effort was by playing football matches themselves, as a means either of boosting servicemen’s morale or of raising money for various war-related purposes. Perhaps the first of these occasions was on 2 September 1915, at Lisburn Golf Club’s entertainment for about 30 wounded soldiers from the Royal Victoria Barracks hospital. As well as plying the soldiers with gifts of cigarettes, the golfers set aside parts of their links for playing crazy golf and skittles, and a ‘very enjoyable’ item of the day was a football match between a team of ladies and a team of soldiers, which ended in a 3–3 draw. On St Patrick’s Day 1917 the Bangor Ladies’ Hockey Club organised a football match at Bangor Recreation Grounds in aid of limbless soldiers at the UVF hospital. The teams—‘Bangor Ladies’ and ‘Ulster Ladies’—played a closely fought match which Bangor won 2–1, a Mrs Chambers scoring the decisive goal from the penalty spot. The match raised almost £7, which included the proceeds of shamrock which the hockey club sold at the venue.

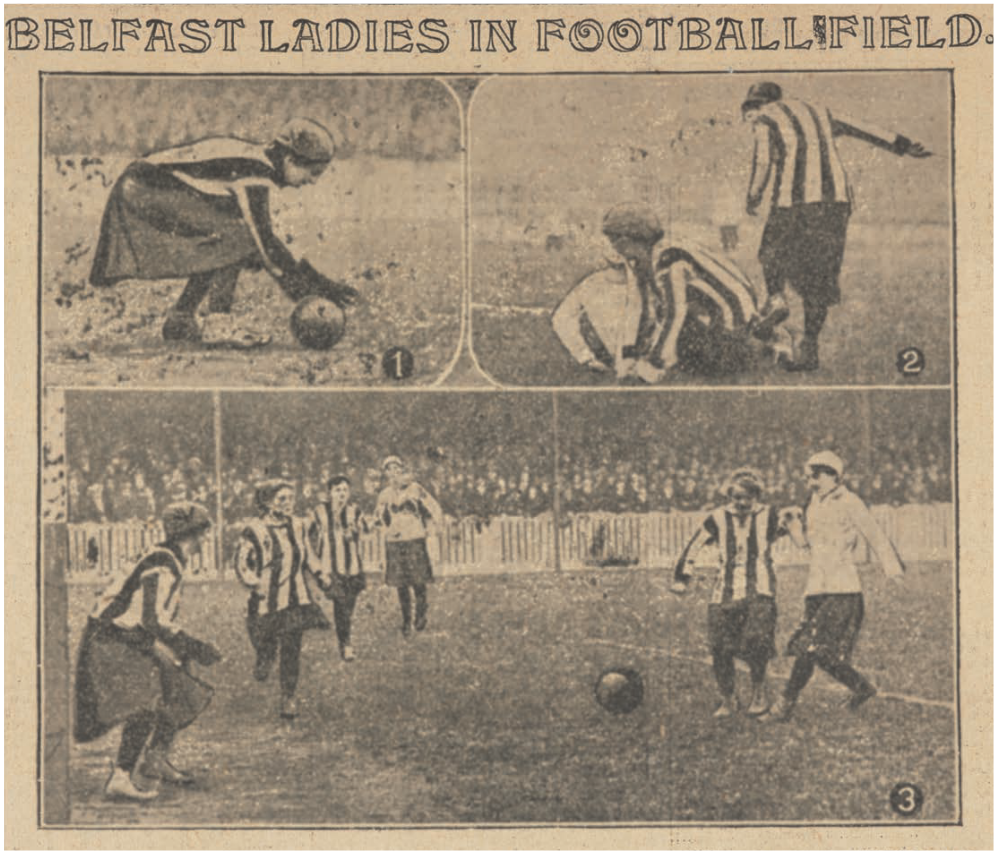

On 7 September 1917 the Footballers’ Guild organised at Grosvenor Park the first of several all-female matches under its auspices. Played between supporters of the Whites (Distillery) and Stripes (Belfast Celtic), the game ended in a 0–0 draw. It was witnessed by an estimated 16,000 spectators, who included ‘the largest crowd of ladies ever seen at a football match’, as well as many soldiers and sailors, with several of the latter wearing blue hospital uniforms. Scott praised both sets of players: ‘They risked ridicule in a good cause and came out winners’. A replay was held at Grosvenor Park a week later, resulting in a 3–0 victory for the Whites. Another large but smaller crowd attended on this occasion, ‘the majority of spectators being of the fair sex fraternity’. ‘Liza Ann’, narrator of Ireland’s Saturday Night’s ‘Chronicles of the Coort’ comical series, commented in Belfast idiom on the sizeable female attendance at the game:

‘Anything lack thon graun’ staun’ ye nivir seen in all yer born days. It wus jist crammed way girls, an’ it wus a regular mask av jade green hats, an’ caterpillar str[e]ams an’ tammy shantirs. It wus lack a regular flour gairden way all the colo[u]rs in the rainbow in it, so it wus.’

The two matches realised some £470 for the Rest Home for Wounded Sailors and Soldiers in Belfast; some of this was raised by selling 1,000 photographs of the teams, which were presented before the second game by the Belfast photographer Robert Lyttle. Diana Scott also helped to organise a ‘burlesque’ football match at Grosvenor Park on 26 September 1917 to raise funds to assist Mary Cunningham of Glencairn in her charitable work for the crews of torpedoed merchant ships, who ‘frequently pass through Belfast in great need’. A team of sixteen women, including two goalkeepers, played a Royal Navy team whose legs were loosely tied together, and the match ended in a 6–4 victory for the civilians. Some 5,000 people attended, contributing £115 to Cunningham’s charity.

OTHER WOMEN’S FOOTBALL TEAMS

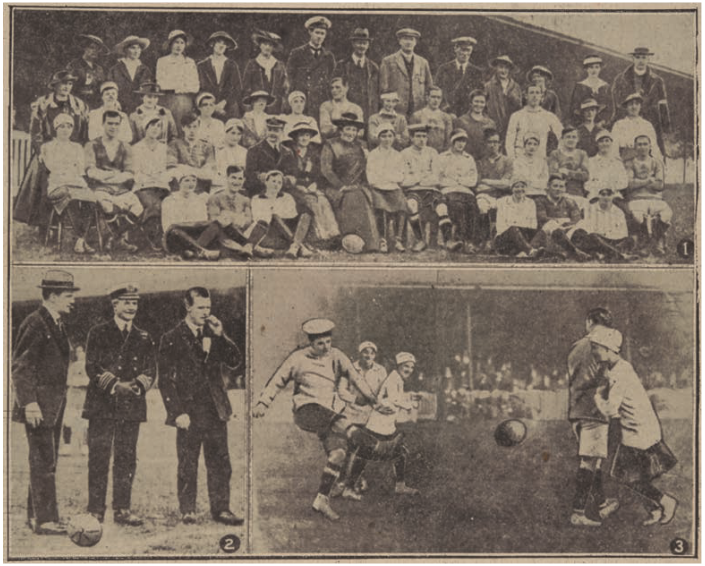

The positive newspaper publicity surrounding the two Belfast women’s teams probably helped in the establishment in late 1917 and 1918 of other women’s football teams who played numerous matches in aid of various war charities. As was the case in England, where so-called ‘Munitionettes’ working in war factories played football in support of the war effort, most of the Ulster women’s teams were formed by factory workers. These included operatives at three Portadown textile and weaving factories: Hamilton Robb’s at Edenderry, Spence Bryson’s at Clonavon and J. & J. Acheson’s Bannview factory. Other works teams were founded by women workers at Lurgan, Banbridge (Walker’s linen mill), Dromore (Murphy & Stevenson’s weaving factory) and Belfast (William Ewart’s Crumlin Road mill). On St Stephen’s Day 1917 an unofficial international match was played at a ‘densely crowded’ Grosvenor Park between an Irish women’s team, ‘so ably stimulated by the exertions of Mrs Scott and her splendid band of workers’, and a team of munitions workers from the north of England. The English team won 4–1, with Ireland’s goal being scored by Lurgan’s Ruby Hall, a machinist by occupation. Hall also scored both of Ireland’s goals in the return match at Newcastle-on-Tyne on 21 September 1918, which England won 5–2. The Irish team, which consisted of eight players from Belfast and one each from Portadown, Lurgan and Enniskillen, at least had the consolation of comprehensively beating their opponents in the sprint races that were held after the football match.

As Diana Scott stated in September 1917, the pioneering Irish women who played football to aid the war effort ‘risked ridicule’ for venturing to play what would have been considered a ‘man’s game’ before this. There is some newspaper evidence that the women footballers were viewed either as figures of fun or as ‘a parcel av husseys kickin’ a ball!! The bould targes’ (to quote ‘Tam’ in the Banbridge Chronicle). Nevertheless, like their wartime counterparts who undertook what would hitherto have been regarded as ‘men’s jobs’, such as working on trams, delivering letters or making munitions, they were soon looked on favourably, at least by that portion of Ireland’s population that supported Irish participation in the war. When ‘Tam’ asserted that ‘Football is a man’s game’, his friend ‘Pat’ replied:

‘Ye mane it’s a workin’ man’s game, Tam; an’ why shudden’t it be a workin’ girl’s game? If workin’ men can enjoy a game av futball after bein’ shut up in a factory all day, A see no reason why girls who hev till work in the same factory shudden’t hev the same privilege. Our workin’ girls can’t go till the Golf Links an’ play nine holes, but our leisured ladies can, an’ do, an’ nobody writes till the clergy about it.’

The evidence suggests that there was public support for women’s football, at least as long as the games were put on for war charities. Teams associated with Mrs Scott played a handful of matches in the immediate post-war years, but there were no efforts to establish women’s football on a permanent footing in this period. It was not until the 1960s that women on both sides of the Irish border began to play football on a regular basis.

Brian Griffin is an adjunct associate professor in Maynooth University’s history department.

Further reading

H. Faller, ‘Part of the game: the first fifty years of women’s football in Ireland and the international context’, Studies in Arts and Humanities 7 (1) (2021), 58–84.

A. Jackson, Football’s Great War: association football on the English home front 1914–1918 (Barnsley, 2021).

G. Newsham, In a league of their own! The Dick, Kerr Ladies, 1917–1965 (London, 1997).