By Cameron C. Engelbrecht

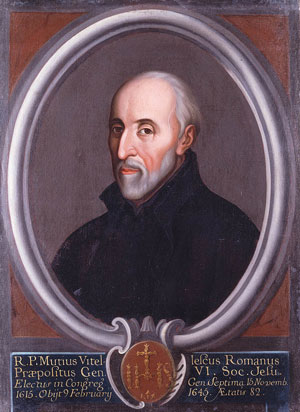

‘If God does not want to, let the devil help me.’ These words are part of the confession of an anonymous noblewoman recorded in the Irish Jesuit mission’s annual letter of 1618, written to Fr Mutio Vitelleschi, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus. These annual letters informed the Superior General on the state of the laity and clergy, the mission’s challenges and other notable events. The letter from 1618, however, is remarkable in that it relates the confession and conversion of a witch. As noted by scholars such as Andrew Sneddon and Elwyn Lapoint, witchcraft was thought by many to be commonplace in Ireland, but trials were few and far between. Moreover, they and other scholars note that both Protestants and Catholics held beliefs in witchcraft in common, and therefore a singular description of a witch is not entirely astonishing. Nevertheless, the fact that contained in this letter is a description of a witches’ sabbat—a phenomenon that is not recorded in any other Irish case and has traditionally been viewed as a feature of Continental witchcraft cases—is astonishing. Moreover, it is also astonishing that this woman was not persecuted but reconciled with the Church. This case is exceptional for both of these reasons and gives us a glimpse into early modern belief in witchcraft and the demonic in Ireland.

This is not a verbatim confession from the woman in question but rather a retelling of what she is supposed to have confessed, according to the author, who remained anonymous. Likewise, we know virtually nothing about this woman. We are only told that she was noble and that she developed a veiled reputation for piety and chastity, all the while concealing her evil nature and taking ‘the devil as her adviser’. Evidently, one of the Jesuit priests caught wind of her activities and examined her, after which she confessed her guilt and how she came to be in Satan’s service.

THE PACT

On the eve of Pentecost 1611, the noblewoman, alone in her room, was ‘distracted by a whirlwind of thoughts’ from which there was no relief for her ‘wounded mind’. In anguish, ‘like a person in despair’, she became angry with God and shouted: ‘If God does not want to, let the devil help me’. No sooner had she finished uttering this ‘ungodly shout’ than a ‘glutton with filthy long black hair … dressed in long dark clothing’ appeared to her. This glutton, the author explains, was none other than Satan himself ‘under the false guise of a man’. During the early modern period it was thought that Satan could take many forms. His portrayal here as a filthy glutton is in line with contemporary conceptions of the devil, which identified him with sin and uncleanliness. In a display of deceptive sympathy, he asked the poor woman what ailed her, but the author does not relate what troubled her. Satan promised her freedom from her agony if she agreed to serve him alone. Terrified at first, she ignored him, but as he persisted she accepted his proposal. Thus she entered into a pact with Satan after renouncing God, her baptism and all things holy.

The pact is what made a witch in learned thought; it was from the pact that a witch gained her power. The reason why a witch entered a pact varied. Often Satan promised revenge or money, but here he offers the woman salvation from her suffering. Moreover, the description of this woman as tormented and ‘wounded’ give us insight into her mental state; perhaps she was suffering from a mental affliction or depression. It is clear that the author believes this to be the reason why she entered into a pact in the first place—out of desperation. It was also believed that the pact had a tangible effect in the form of a witch’s mark. What were in reality birthmarks, scars, warts etc. were believed to be a sign of a demonic covenant and were tested by pricking or lancing. If the area did not bleed or seemed impervious to pain, it was considered a witch’s mark and was used as evidence of the accused’s guilt. The woman in this case had a mark shaped like a playing card on her left hip, but she does not appear to have been subjected to pricking of the area.

THE SABBAT

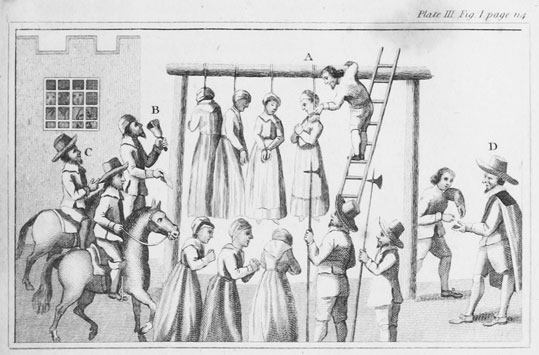

Sometime after their first meeting, the woman broke her promise to Satan, likely by worshipping God once more. Soon after, Satan appeared to her again and invited her to the ‘place of pleasure’, otherwise known as the sabbat. In the dead of night, the woman was carried away to a remote location on a goat. Upon her arrival, she was brought before Satan in the form of a ‘hideous monster, seated on a throne’, and commanded to adore him, recommit herself to him and denounce God once more. Once she had done this, another witch or a demon grabbed her, baptised her with ‘some stinking liquid’ and endeavoured to scrape the chrism from her forehead with their nails. Afterwards, Satan presided over an inversion of the Mass using a piece of root covered in soot, which she was made to distribute to those present. Finally, Satan ‘transformed into the likeness of a she-goat … [and] exposed his posterior, pouring out flames to all the obedient ones and blow-kissing blasphemous shouts against God towards [those present]’. Kissing Satan’s posterior was a common sign of submission in sabbats. After these rituals, those gathered held a party and banquet, during which they danced and ‘performed many other obscenities’. The author gives no clue as to what exactly these were, only that the ‘shock of it’ does not allow him to recount them. Judging from other accounts of sabbats, however, it is likely that these obscenities included orgies with the other witches, demons and Satan himself, as well as infanticide, cannibalism and the concoction of magical balms used for a variety of purposes. The woman, along with demons and other witches, attended the sabbat every Monday and Friday.

The sabbat is a typical scene in demonological writings and accounts of witchcraft trials. Above all, the sabbat was an inversion of the core features of early modern society, namely the worship of God and the Mass or other religious services. It has long been considered uncommon in England or Ireland, although historians such as James Sharpe have challenged this assumption. Nevertheless, the sabbat’s appearance in English and Irish trials is still thought to be rare. Some have argued that the lack of a sabbat and the relative absence of the devil in English cases can be explained by the fact that most people were not concerned as much with the demonic aspects of witchcraft as with its tangible effects, which brought possession, harm and the death of both humans and livestock. It is therefore curious that it appears here.

There are a number of possible explanations as to why the sabbat appears here. First, it is essential to note that the sabbat was not unheard-of by the ordinary people in Ireland (or England, for that matter); they likely came to know of it through preaching, stories or cheap, mass-produced pamphlets. It is entirely possible that the woman read about the sabbat in a pamphlet or book or learned of it by some other means and came to the confession on her own. Another possibility relates to the Jesuits’ background. The Jesuits more than likely had prior knowledge of the sabbat, which they either learned or developed on the Continent during their education and then brought back to Ireland. Scholars of Irish witchcraft, such as Sneddon, Lapoint and Maeve Brigid Callan, have argued that witchcraft cases in Ireland exhibit characteristics synonymous with beliefs held by the communities in which they arose. While the woman in question was not accused, she was ‘examined’ by a Jesuit priest who likely had knowledge of the sabbat. It is possible that the woman was influenced to confess to attending a sabbat through leading questions posed by the priest or that the priest simply interpreted her confession in this way. One can only speculate, however; the answer is ultimately unknowable.

RECONCILIATION

The woman confessed that she spent seven years as a witch in the service of Satan. While she was able to conceal many of her nefarious deeds, she let slip signs of her ‘bewitched immodesty’ and ‘dissolute behaviour’. Her mother began to notice these signs and rebuked her for her behaviour, to which the woman did not take kindly. After consulting with another witch, she attempted to murder her mother with poison several times. Poison was believed to be a common method used by witches to murder their victims. Fortunately, and by the grace of God, as the author explains, the poisonous cup was always poured out before her mother could drink from it, so her attempts failed.

Eventually, a priest uncovered her deeds and she confessed to them, but instead of condemning her as a heretic, or trying her criminally under the Irish witchcraft statute of 1586, the Jesuits assisted the woman in her conversion. The priest was advised by his superior to ‘try to appease the spirit not so much with many prayers as with fasting and by freely flogging the body’. Satan, however, continued to appear to the woman, particularly after the sacrament of penance, threatening her with harm and promising to reward her should she return to him, which she did once and attended the sabbat once more. To rectify this, the priest employed the use of saints’ relics and a ‘blessed lamb made from wax’. The author ends his letter by informing Vitelleschi that, through this procedure and frequent participation in the sacraments, the woman now leads a life of virtue. This leaves us with a confounding question: why is it that this woman, who admitted her guilt, was not prosecuted nor persecuted as were thousands like her across Europe?

CONCLUSION

The most likely answer stems from the purpose of the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits were the agents of the Counter-Reformation, formed to combat the spread of Protestantism and heresy, such as witchcraft, through the administration of Catholic doctrine and the sacraments and by reconverting those who had left the Church. To do this effectively, the Order was granted special privileges. One such privilege was the ability to absolve penitents from heresy, granted by Pope Julius III in his Sacre Religionis in 1552. The Jesuits may have thought it more advantageous to absolve the woman from her crimes than to persecute a member of their flock, which was under pressure to conform to Protestantism. After all, she confessed her crimes freely and entered into a pact out of desperation and anguish, both of which could have mitigated her guilt and restrained the Jesuits’ response.

Moreover, given that she was a noblewoman, it is possible that the Order was receiving shelter or financial assistance from the woman or her family, and they did not wish to strain that relationship. It is important to remember that the Jesuits were not welcome in Ireland; they had to live secretly, and persecuting a witch would have undoubtedly drawn unwanted attention from the English authorities.

Elwyn Lapoint also provides us with another possible answer. He has suggested that, in general, the number of formal witchcraft accusations and trials in Ireland remained low because the Irish refused to bring accusations before an English court as a form of social protest. While Raymond Gillespie has argued against this theory on the grounds that the Irish used the courts willingly in many other cases, it is possible that the Jesuits were doing something similar. Perhaps they felt that to turn this woman over to the authorities to be tried would be a recognition of a Protestant authority. Again, there is a myriad of possible explanations but the question ultimately remains unanswerable because of the lack of further details.

Whatever the reason, this letter gives us an important and intriguing piece of evidence for the study of witchcraft in Ireland during the early modern period and supports many of the arguments previously posed by scholars of the subject. Moreover, while this is the most fascinating mention of witchcraft in Vera Moynes’s (ed.) Irish Jesuit Annual Letters, it is not the only mention contained in the series’ two volumes, providing historians of witchcraft in Ireland and Europe with important new sources for further study of the subject.

Cameron C. Engelbrecht has an MPhil. in Early Modern History from Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

M.B. Callan, The Templars, the witch, and the Wild Irish: vengeance and heresy in medieval Ireland (Ithaca, 2015).

E.C. Lapoint, ‘Irish immunity to witch-hunting, 1534–1711’, Éire–Ireland: A Journal of Irish Studies 27 (1992), 76–92.

Vera Moynes (ed.), Irish Jesuit Annual Letters 1604–1674 (2 vols) (Dublin, 2019).

Andrew Sneddon, Witchcraft and magic in Ireland (London, 2015).