By Cormac Moore

The Irish Boundary Commission, which was provided for under the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, collapsed almost four years later, in late 1925, without any changes having been made to the border. The fallout still resonates deeply today.

UNIONISTS FAVOURED OVER NATIONALISTS

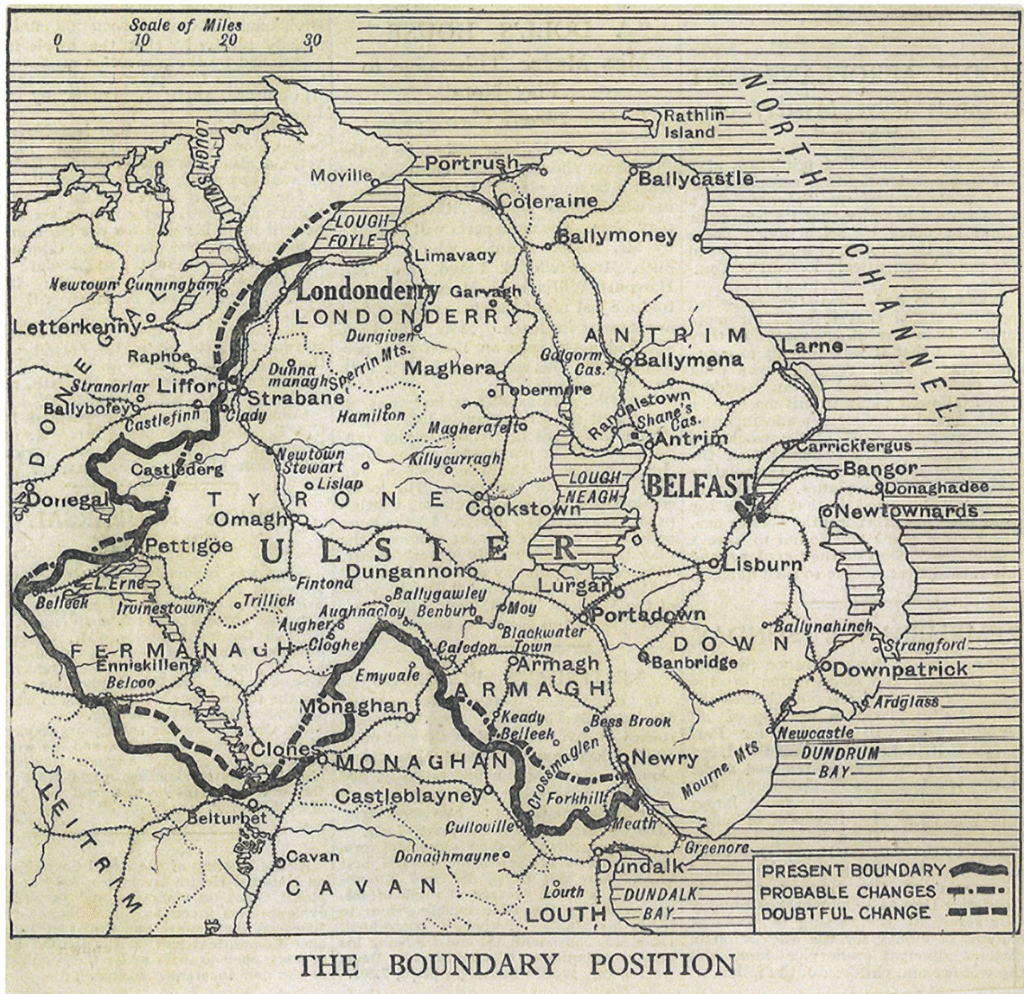

Following the formal interviews of almost 600 people from March to July 1925, during the summer and early autumn of 1925 the Boundary Commission set about redrawing the border. A series of meetings were held from late September, culminating in one on 17 October when an award was substantially agreed upon by the Commissioners. Showing his dominance on the Commission, the award reflected the conclusions that the chairman, Justice Richard Feetham, had submitted to the other Commissioners, Joseph R. Fisher (representing Northern Ireland) and Eoin MacNeill (representing the Irish Free State), in a memorandum on 11 September 1925. The main draft conclusions that he reached included that the existing boundary line could be shifted in either direction; that Northern Ireland must, when the boundaries had been determined, still be recognisable as the same provincial entity; that the wishes of the inhabitants ‘are made the primary but not the paramount consideration’; that inhabitants ‘means persons having a permanent connection with the area concerned’; and that the Commission should be ‘prepared to take as a unit of area in relation to which the wishes of the inhabitants are to be ascertained the smallest area which fairly be entitled … to be considered separately’, and not large areas such as counties or Poor Law unions. Practically all of Feetham’s conclusions favoured the unionist over the nationalist case.

The draft award recommended the transfer of parts of east Donegal and north Monaghan to Northern Ireland, and parts of Tyrone, Fermanagh and south Armagh to the Free State. In total, 183,290 acres and 31,319 people (27,843 Catholic and 3,476 non-Catholic) were to be transferred from Northern Ireland to the Free State, and 49,242 acres and 7,594 people (2,764 Catholic and 4,830 non-Catholic) were to be transferred from the Free State to Northern Ireland. It fell far short of nationalist expectations, with many hoping that most of counties Tyrone and Fermanagh, south Armagh and south and east Down, as well as Derry city and Newry, would be transferred to the Free State.

The Boundary Commission recommended that Derry city and Newry remain in Northern Ireland. The omission of Newry (with an almost 75% Catholic/nationalist population) from the Free State was unquestionably Feetham’s most egregious decision and made little sense even under the convoluted rules that he had concocted.

What is most surprising about the recommended award is not that such an award was made (the writing had, after all, been on the wall for some time) but that MacNeill appears to have consented to it—or, at the very least, made no substantial objection to it.

MORNING POST LEAK

There had been much speculation in the press on the potential new boundary line while the Commission was deliberating. It was the projected award published in the conservative Morning Post (later merged with the daily Telegraph) on 7 November that went beyond a mere prediction. Its forecast was so close to the actual award that most people since have assumed that Fisher leaked it to the newspaper, something to which he never admitted.

The Morning Post forecast did not seem to perturb the Free State Executive Council or MacNeill initially, but once border nationalists started to protest and express their anger at the abysmal forecast, it soon dawned on the Free State government that it was facing a political crisis of great magnitude. On 20 November MacNeill resigned from the Boundary Commission, claiming ‘that a situation of extreme gravity had arisen in Ireland consequent on the Morning Post revelations’.

In their subsequent statements to the press, Feetham and Fisher claimed that, before his resignation, MacNeill ‘had made perfectly clear his intention of joining with us in signing the Commission’s Award embodying a boundary line the general features of which were approved and recorded in our Minutes as long ago as Saturday 17th October’. MacNeill was then forced to take the only other action left to him and resign from the Executive Council.

It is important to acknowledge that MacNeill’s position was incredibly difficult; no matter who the Free State commissioner had been, it was unlikely that the aspirations of the Free State government, and particularly of border nationalists, would have come close to being met. Nevertheless, his performance throughout the Boundary Commission, and even after the Morning Post report, made what was a difficult position infinitely worse. When the Free State government tried to negotiate its way out of the mess in which it found itself, the blunders of MacNeill weakened its hand from the outset.

The president of the Free State Executive Council, W.T. Cosgrave, rushed over to London to have the Boundary Commission report buried. While Cosgrave had previously shown empathy for the plight of Northern Catholics, with an opportunity to have Article 5 of the Treaty waived he jettisoned their interests to save money for the Free State. Article 5 stipulated that the Free State was liable to contribute to servicing the public debt of the British Empire and to the payment of war pensions, which could have cost in the region of £150,000,000. Cosgrave even went as far as to contradict his Executive Council colleague Kevin O’Higgins in negotiations with Northern Ireland prime minister James Craig. After O’Higgins suggested that the proportional representation (PR) system of voting be restored in Northern Ireland, Cosgrave incredibly sided with Craig in opposing its reintroduction, saying, ‘For my part I’d like it out of the way’.

‘LONDON AGREEMENT’

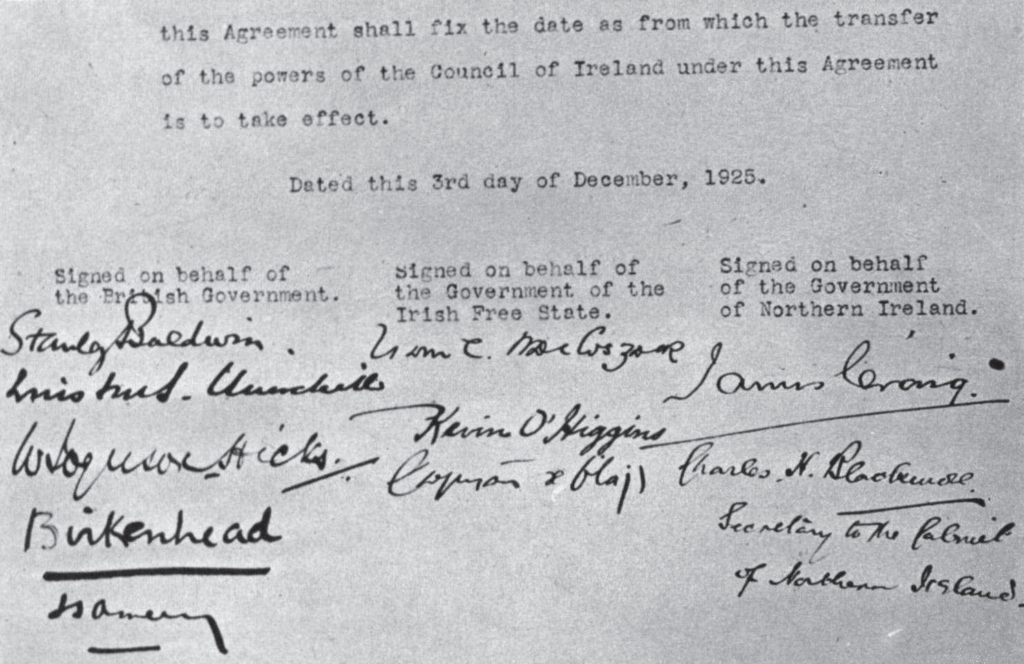

After a week of intense negotiations involving the Free State, British and Northern Irish governments, a tripartite agreement was signed on 3 December 1925. Under this agreement, Article 12 of the Treaty was revoked and Northern Ireland’s boundary remained as it was defined under the Government of Ireland Act, 1920; Article 5 was waived for the Irish Free State; the Free State became liable for malicious damage incurred during the War of Independence; and the Council of Ireland was scrapped.

Despite describing what became known as the London Agreement as a ‘damn good bargain’, Cosgrave was fooling few people. Wilfred Spender, head of the Northern Ireland civil service, later claimed that Cosgrave did not believe it was a good bargain and that during a meeting with Craig he ‘burst into tears and said that Lord Craigavon had won all down the line and begged and entreated him not to make things more difficult for him’.

Twenty copies of the Boundary Commission’s report with its proposed award were deposited at the British Cabinet Office. All others were destroyed. The report remained sealed for over 40 years. The British government opened the files to the public on 1 January 1968, with Geoffrey Hand publishing his edition of the report the following year. The contents of the buried Boundary Commission report were revealed to the public just as the problem it had failed to resolve flared up again with the start of the Troubles.

EOIN MACNEILL—‘INERTIA, INCAPACITY, AND APPALLING INEPTITUDE’

Eoin MacNeill tried to rehabilitate his political career somewhat when he unsuccessfully ran for election as a TD in June 1927, claiming then that ‘[The] thing that mainly made the Boundary Commission fruitless was the defective character of Article 12 of the Treaty’. There are some merits to his argument. The ambiguous wording of Article 12, whether by fault or by design, was at the heart of most of the problems that nationalists subsequently encountered over the following long four years. The Sinn Féin plenipotentiaries were at fault for agreeing to such vague wording, while the British negotiators probably designed the clause in such a way as to offer them manoeuvrability options on which they readily capitalised.

Regardless of the sizeable obstacles that he faced, it is hard to disagree with the Derry Journal’s assessment that MacNeill’s performance was marked by ‘inertia, incapacity, and appalling ineptitude’. For much of the Commission’s proceedings he embodied the caricature of the absent-minded professor, seemingly disinterested in what was happening around him. By not strenuously objecting or issuing a minority report to the proposed Boundary Commission award, and by the manner of his resignation from the Commission and then from the Executive Council, he turned what could at least have been a propaganda win for the Free State into one of containment of a potentially terminal crisis for his government.

PARTISAN CHAIRMAN

From a nationalist perspective, arguably a bigger problem than the ambiguous wording of Article 12 was the fact that the British government chose the chairman of the Commission. The wording of the clause was similar to the wording of other boundary commissions in Europe at the time, after all. However, all of those were convened by independent chairmen. It is hard to ignore the unfairness of Feetham’s proposed award and how all his interpretations favoured the unionist over the nationalist cause.

The long delays in the convening of the Boundary Commission lessened the prospects of a favourable outcome for Irish nationalists. The delays were caused by the Civil War in the Free State, political instability in Britain (there were three general elections and four prime ministers between late 1922 and late 1924), and particularly by the Northern government’s refusal to recognise the Boundary Commission. The two-year delay was compounded by Feetham’s decision to consider conditions as they were in 1925 and not in 1921.

W.T. Cosgrave’s Cumann na nGaedheal government took seriously the Boundary Commission, as well as its pursuit of a united Ireland, certainly up to the tripartite agreement negotiations in late 1925. The dedication of the staff and the scale of the work completed by the North Eastern Boundary Bureau that Cosgrave established in October 1922 were laudable. The work, however, was often directionless, based on suppositions that did not hold true. It made many wild assumptions, on which it based much of its extensive output. For example, the Boundary Bureau, like the Sinn Féin leadership since 1918, failed to understand that Ulster unionists hated Dublin more than they loved the British Empire, their attachment to which was often conditional.

The Cumann na nGaedheal government survived the crisis created by the breakdown of the Boundary Commission but it was severely damaged. TDs resigned from the party over the issue. The ineffectiveness of the Sinn Féin abstentionist policy was brought home to Éamon de Valera as the crisis over the Boundary Commission unfolded. Months later, he left Sinn Féin and formed Fianna Fáil, which went on to dominate politics in the 26 counties for decades.

British governments from 1921 to 1925 acted to deceive nationalists and to ensure that the outcome of the Boundary Commission would favour unionists by only recommending cosmetic changes to the border. They did this by ensnaring Sinn Féin into agreeing to a vague clause in the Treaty, by stalling on the convening of the Commission, by promising unionists that no substantial changes would be made to the border regardless of the Commission’s recommendations, and by appointing conservative and unionist commissioners who were never going to agree to an extensive rectification of the border.

JAMES CRAIG THE BIG WINNER

The 1925 London Agreement was a triumph for James Craig more than anyone else. Under enormous pressure, both internal and external, he steadfastly stuck to his ‘not an inch’ strategy and refused to recognise the Boundary Commission, publicly at any rate. Not only did the tripartite agreement secure Northern Ireland’s existing borders but also the ‘irritating’ Council of Ireland was abandoned. Craig, with his popularity soaring after the London Agreement, had a perfect opportunity to be magnanimous towards the nationalist minority. He chose not to be, governing solely for the benefit of Ulster unionists instead, leaving Northern society to remain bitterly divided. While the border issue was ‘settled’ by late 1925, divisions remained as malignant as ever.

The Boundary Commission was an unsatisfactory solution for almost everyone, but for border nationalists on the Northern side it had offered real, tangible hope. The slow and steady sapping of their rights and influence in the early years of partition had a devastating effect on their morale and confidence. They clung desperately to the hope of being released from their burdens and were shattered when the Boundary Commission did not deliver for them.

The fallout from the Boundary Commission has left a bitter taste in the mouths of Northern nationalists ever since. Their trust in British governments (always threadbare) evaporated completely. Perhaps more importantly, their trust in the South suffered an irrevocable blow owing to the Free State government’s abandonment of the North for financial benefits. That mistrust still resonates today.

Cormac Moore is a historian-in-residence with Dublin City Council and a columnist with the Irish News.

Further reading

G.J. Hand, ‘MacNeill and the Boundary Commission’, in F.X. Martin and F.J. Byrne (eds), The scholarly revolutionary: Eoin MacNeill, 1867–1945, and the making of the new Ireland (Shannon, 1973).

C. Moore, ‘The root of all evil’: the Irish Boundary Commission (Kildare, 2025).

P. Murray, The Irish Boundary Commission and its origins (Dublin, 2011).